Victoria Ruffin Atkins turns and faces the several dozen teenagers standing in parallel lines on the Goldsboro High School auditorium stage.

Moments earlier, they were all smiles — joking with their choral director backstage as they prepared to perform for a full house — but when the light hits Atkins’ face, they can tell by her expression that it’s time to get serious.

To the GHS Show Stoppers, this particular song is not just another track on their set list.

It has, in many ways, become both their anthem and Atkins’ way of preaching to her alma mater through her students.

But to make them — their peers, parents, community leaders, and others in attendance — buy into the message they are attempting to deliver, they know have to own every single word.

“When the sharpest words wanna cut me down

I’m gonna send a flood, gonna drown them out.

I am brave, I am bruised

I am who I’m meant to be.

This is me.”

Watching Atkins command respect from the boys and girls in the choir she ran at GHS for years, it was clear to both those inside the historic Beech Street building and people who saw them perform everywhere from retirement homes to the Wayne Regional Agricultural Fair, that with the right mentor, students in Wayne County’s lowest-performing school could shine.

And when they sang those words, it was clear that after a lifetime of attending failing schools and navigating the challenges associated with growing up in some of Goldsboro’s most impoverished neighborhoods, it also took the right leader to convince them that was the case.

“I always tried to instill in my kids that they could defy all those labels. There is always going to be a label somebody is going to try to place on you because you come from a single-parent home or because you live in a certain project,” Atkins said. “I lived in those areas and look at me. So, when students came to me, they knew when they crossed the line into my classroom, those labels went away. You came to me to be the best you that you could be, and I treated them as such. I had high standards and they followed suit. You have to treat them as the best and they will give you that.”

They proved it on stage, yes, but also when they organized to blow the whistle on deteriorating conditions inside their school during a 2022 City Council meeting — a presentation that resulted in statewide news coverage, visits from legislators, and almost immediate work by the school district to fix everything from rotting ceilings and floors to plumbing issues and insect and rodent infestation.

Atkins, a GHS graduate who left Wayne County Public Schools at the end of the 2022-23 school year to pursue her dream of working as an administrator, has been thinking about them lately — ever since the Wayne County Board of Education unanimously voted, without specifying on its agenda action involving the school could unfold, to move the GHS student body out of their historic home and into the building currently occupied by Wayne School of Engineering.

She wonders who might have shown up to talk about the fear she says has set in among students and alumni as a result of that vote — that this is simply the next step in what will, one day soon, culminate in the end of the school she attended and taught inside.

“I am so disappointed about it because … I don’t think that any new superintendent — any new anything — should just come to Goldsboro and say, ‘This is what we’re going to do,’ and slide it in and not include the alumni and community input,” Atkins said. “I feel like there is a bigger plan in place. I really feel like they are trying to do away with Goldsboro High School altogether.”

She is not alone.

In the nearly a month since the Board of Education voted to approve a “Facility Utilization Plan” that included relocation of four schools — GHS, Wayne Middle/High Academy, Wayne School of Engineering, and Edgewood Community Developmental School — a common theme in social media posts, inside churches and restaurants, and around watercoolers is the fact that none of those schools were mentioned on the agenda released ahead of the Feb. 5 meeting as part of WCPS’ legal obligation to notify the public of the official business that would be discussed.

“We had no idea until it was already said and done,” Atkins said. “I feel like by Goldsboro High School being such an historic landmark, by us having one of the biggest alumni organizations in the world, that is something they should have gotten our input on. But they didn’t want it. They have never wanted it. I mean, let’s just say they knew what they were doing.”

Once counted among the top high schools in North Carolina, it has been a rough two decades for GHS.

Back in 2006, Judge Howard Manning named it as one of nearly 20 schools across the state that would be closed if they did not improve.

And in 2016, the N.C. Board of Education approved “Restart” status for the school — a move some saw as a “last-ditch effort” to save GHS.

Under the Restart model, “recurring low-performing schools” are given flexibility in both how they staff their buildings and how they deliver education.

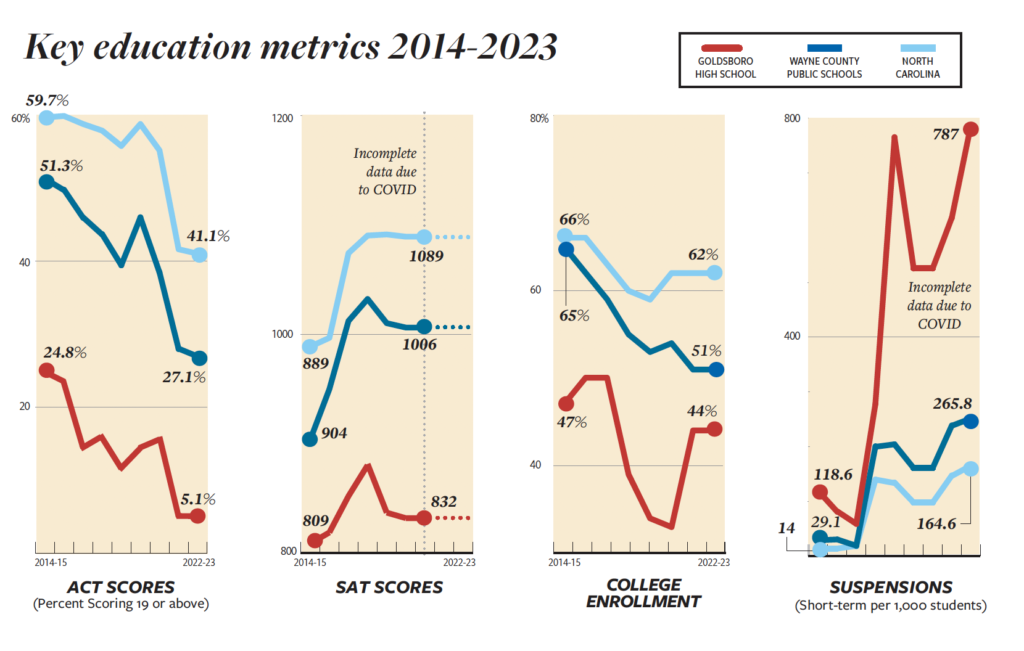

But in the years since GHS received the designation, the numbers have gotten worse.

In its first year under the Restart model, the school earned a D on its state report card and a “performance grade” of 42.

Only 14.4 percent of students scored a 19 or higher on the ACT — 44 percent below the state average — and only 50% of graduates went on to enroll in college.

And the short-term suspension rate, another metric reported on state report cards, was 81.15 per 100 students. By comparison, the state average was 14.02 and the Wayne County Public Schools average was 29.20.

Last year, the school received an F with a performance score of 38.

Only 5 percent of students scored a 19 or above on the ACT and 44 percent enrolled in college.

And the short-term suspension rate was a staggering 787.04 per 100 students.

In fact, little academic improvement was demonstrated during any year between the school’s first year of Restart and today.

In response to a question submitted to WCPS by New Old North, district spokesman Ken Derksen said Central Office leaders recognize that “GHS has not realized the academic gains originally hoped for through the Restart model.”

“The district administration is carefully looking at what may need to be done differently moving forward to best leverage Restart flexibilities to advance the school and to make greater academic gains if Goldsboro remains in Restart,” he added.

And at the same meeting at which board members voted to move GHS students to what is currently the home of Wayne School of Engineering, they also approved submitting a new Restart application to the state.

Superintendent Dr. Marc Whichard, during an hourlong sit-down with New Old North, said he was confident that GHS would be granted another chance to succeed under Restart.

“I have good faith that it will be approved,” he said, before declining to answer what would happen if the state rejected the application. “We’ve made significant changes there.”

Inside his classroom on the GHS campus, Taj Polack tried to take time every single day to address, head on, the challenges his students face.

The way they dressed and spoke to adults would matter more because of the neighborhoods they grew up in.

Their actions would be scrutinized more because they attended the lowest performing high school in the county.

And if they weren’t careful, he told them, one day, his alma mater would cease to exist.

“It seems like this is something that’s been in progress for years. This isn’t a new thing. I actually talked to my students … and told them I could foresee something of this magnitude occurring,” Polack said. “I always felt like at some point, they were going to shut down Goldsboro High School. I could see the writing on the wall.”

But what disturbs the now-former teacher more than the decision to move the student body is what he considers a lack of transparency by the Board of Education.

A former member of the Goldsboro City Council — and, for a period, its mayor pro tem — he said not specifying the potential of a GHS move on the board’s Feb. 5 agenda all but ensured hundreds of alumni, students, and stakeholders he believes might have otherwise shown up to sound off on the change were left out of the conversation.

And at the very least, board member Patricia Burden, a former GHS principal, should have notified the Dillard/Goldsboro Alumni & Friends.

“I think the mere fact that we thought we had representation for our school, and we didn’t, it was a travesty. We had no representation. I think the public should have been informed about something of this magnitude,” Polack said. “And the people that everybody has touted as the advocates for our community are not representing us and it shows. Their votes speak.”

But he is not surprised with how the school board voted.

After all, he said, they have known about problems at GHS for years and turned a blind eye, only taking action when Atkins’ students blew the whistle about conditions inside the building.

“We saw the writing on the wall. We saw the upgrades being done on the School of Engineering side while we were dealing with — until it was exposed by a group of students — a dilapidated structure,” Polack said. “And they have known about the other problems and did nothing. They knew that, even as an instructor, I was told to give certain students preferential treatment because they were athletes. That is a fact. So, them not doing right by that school, it’s nothing new.”

And they are also responsible, he said, for what is seen by many as a lack of stability inside the school, as teachers and administrators seem to come and go more so than on any other WCPS campus.

“In 10 years, we haven’t had any stability at that school as far as leadership. In the era of my mother being a teacher there, Mr. Pat Best literally put that school and the well-being of those students above his own family,” Polack said. “We haven’t had a leader like that in a long time and it’s sad.”

Atkins agreed.

The way to begin to turn the tide at GHS is through leadership, not moving buildings.

“Something needs to change but stop putting the wrong people in place in that school. You need to find someone who has the heart for that school, the heart for that community and who will bring in people who want to come into that building and turn it around — not throw it to the side,” she said. “It takes time. It’s going to take more time for Goldsboro High School to … arrive academically. But it’s never going to happen if you don’t have the right leader in place. Without a leader, the building doesn’t matter and by moving those students, all you’re doing is making them feel worse without a leader to guide them forward.”

And transitioning the student body into a smaller school facility also means GHS will not be able to receive something Polack and Atkins agree could truly change the fortunes of the school they love — more students from other areas of Wayne County that could diversify the campus.

“Of course, on redistricting. We know we need to have different cultures and different races and different academics in that school. If we don’t, it will only get worse,” Atkins said. “We know GHS and our inner-city schools serve like nine housing projects, but there still has to be a way where we can integrate different cultures and races into those schools. Goldsboro, is doesn’t have to be an all-black school. That’s just the way they have redistricted so it would be that way. But I really do believe they need to have more culture there.”

Polack took it a step further.

In his view, the segregated education he said exists at GHS — no matter the building that houses it — is damaging the city he was once elected to serve.

“When I was a student, it was a 60/40 blend. The scores were higher. And I’m not saying they were higher because we had more white kids. They were higher because the integration, in and of itself, gave us morale and pride. We have lifelong friendships with people from different backgrounds which now, you don’t see that,” Polack said. “And that right there is creating a whole culture in this city that we don’t need. Now, these kids are growing up not experiencing these other kids’ backgrounds and when they become adults, they are going to have this divisive mindset. It’s dangerous.”

And if his community wants to be taken seriously when it shows up to the Board of Education’s March 4 meeting, he said it has to look in the mirror about another factor he says led to GHS being vulnerable to decisions like the one made in early February in the first place — and could, he fears, soon lead to “the end of GHS as we have known it.”

“You’ll notice that on Open House night, you can count the small number of cars in the parking lot,” Polack said. “But let there be a basketball game or a football game and the parking lots are full. That speaks volumes.”