For Charlie. For Dad.

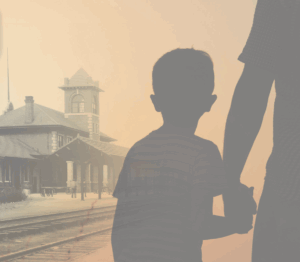

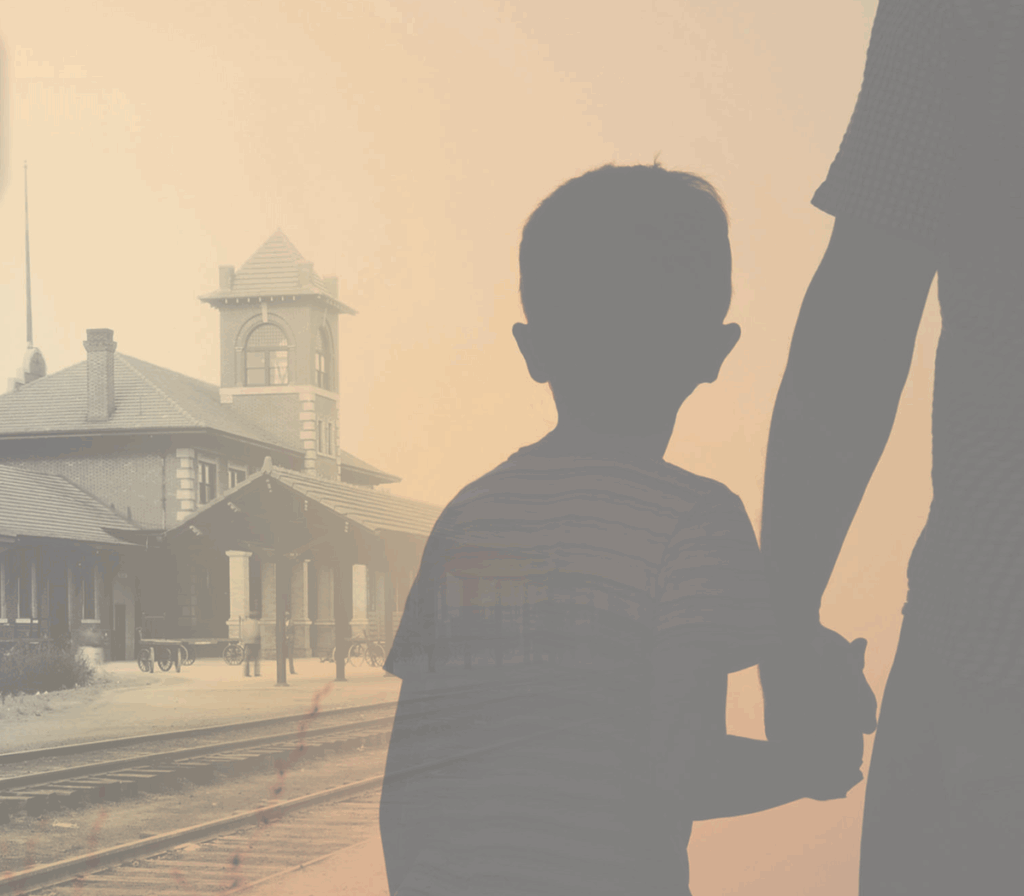

Editor’s Note: On Tuesday, Oct. 7, New Old North Editor Ken Fine jumped into a pickup truck and rode around Goldsboro as Mayor Charles Gaylor took him on a tour of some of the places that meant a great deal to his late father. During the ride, Fine learned a great deal about the relationship between father and son — and why, after several weeks of consideration, Gaylor and his mother, Rhonda, reluctantly decided to allow the Saving Union Station group to raise money for stabilization of the historic depot in the late judge’s memory.

Charles Gaylor IV turns onto Virginia Street and the memories start playing.

There is the yard that he and other children from the neighborhood chased each other around in “all the time.”

There is one of the houses his father and a group of friends bought, restored, and sold.

There is the train station that provided the soundtrack as he fell asleep during his childhood.

With the exception of the sprawling yard, the landmarks have changed since the first time he traveled this particular route.

And back then, he was not the driver.

He was a little boy — a first-grader — whose father was navigating an indirect track to his son’s school.

“We would have to leave the house early because he had the keys to, like, the Weil houses, for example. He would take me to go unlock the doors and get the contractors going to do restoration jobs, and then he would go and drop me off at school,” Gaylor said. “I couldn’t even tell you how many times that was the case.”

But for the late Charles Gaylor III, a former judge, philanthropist, and local historian, ensuring his son — his namesake — saw firsthand what it took to be a part of preserving the city that raised him was not about boasting about all he was doing for his community.

He was, in his mind, laying a foundation so that one day, he could pass the torch to the next generation.

For the elder Gaylor, every home he rehabilitated sent a message to his son — one he hoped he would then pass on to his own children.

Those who live in the present are keepers not of the structures, but of the memories made inside them.

So, it was not surprising when his son stopped his truck in front of one of the many houses located inside the Goldsboro Historic District that would, in all likelihood, soon be razed.

“He would see something like this right here, and he would go, ‘OK. What is the history of this house? Look at that front door with those three emblems,’” the younger Gaylor said. “He would point out, ‘That right there tells you that whoever built it was intending for it to be ornate — intending for it to be a piece of history that was going to be there longer than them. They’d never built it thinking that it would basically become a pile of abandoned wood.’ Things like that would drive him nuts.”

•

Watching his son come of age, Judge Gaylor never imagined that he would, one day, be elected Goldsboro’s mayor.

Sure, the family’s history of service — and success at the polls — were well-documented.

Yes, he believed that Charles could be an effective leader and continue the tradition of working to leave the city a better place than it was the day he was born.

But for him, the reason it brought him joy had nothing to do with adding another Gaylor to the city’s history books.

He saw it as a chance for Charles to continue his work — to “give future generations the opportunity” to bring Goldsboro back to its glory days.

So, when it came time to vote to fight to save Goldsboro Union Station, Charles heard his father’s voice.

“A lot of what he would say was you take on a preservation project not to see it through, but so that you’re leaving the option for someone else to fix it. Because if you’re tearing it down, you know good and well that another one’s never going to get built,” the mayor said. “You’re not allowing the next generation that might be able to find a way to get it across the line that opportunity. And I have no doubt in my mind that the approach of stabilizing Union Station — just to at least ensure that that option stays on the table for whoever comes next — I know he’d stand by that, because we don’t know what the future holds unless we make a really, really firm decision to rob ourselves of the potential for a future.”

And that is why, after the judge passed earlier this year, Charles and his mother, Rhonda, reluctantly agreed to allow members of the Saving Union Station group the ability to fundraise for stabilization and restoration of the depot in the elder Gaylor’s memory.

He had been at the site leading guided tours last summer — a June day when there was not a cloud in the sky to provide relief from a 100-degree afternoon for attendees who showed up to consider making a donation to the “Save Union Station” effort.

“Wearing a suit,” Charles said, a smile creeping across his face. “And loving it.”

He and Rhonda had purchased a home before their son was born that those standing in front of the depot could see at the top of the hill.

“I fell asleep hearing trains,” Charles said. “Maybe that was part of it.”

But the mayor does not believe his father’s passion about Union Station was really about the train station, itself — at least, not entirely.

“I think a bigger part of it was seeing something that is currently underutilized that needs to go back to being a community asset. And it was, and it is, on the brink, and you cannot replace something like that,” Charles said. “Dad really, really, really believed that you don’t need to have things that are wasted. He also really, really believed that when you’re dealing with things like that train station, like City Hall, like the house that he grew up in and the house that I grew up in, you’re merely a steward of that property for some period of time. And if you look at something and go, ‘Oh, we don’t need it anymore,’ and tear it down, you lose something you can never get back.”

•

Save a few words of thanks at the City Council meeting immediately following his father’s death to those who had wrapped their arms around the family after his sudden passing, Charles has not spoken publicly about the loss.

And during that Tuesday ride, it became clear just how much he still misses a man he considered a hero.

Tears formed in his eyes, and he looked out the window into the distance when he talked about how every Saturday, the two went to breakfast together — sometimes, at the Lantern Inn, and others, all the way in Mount Olive or Fremont.

“Some mornings we would talk about, you know, State versus Carolina. Other mornings, we would talk about something else. But it was every Saturday,” Charles said. “And I was too young to fully appreciate it.”

Those same eyes beamed with pride when he talked about ensuring that he and his son, Charles V, had their own special traditions.

“I love being a dad,” he said. “I will sit there and we will go into practice mode on Madden and we’ll do two controllers and … play for hours. … And you know, I love coaching Charlie’s soccer team and baseball team.”

But perhaps, most of all, he treasures the fact that his son is old enough to see the sacrifices his father is making to be a part of Goldsboro’s future — that in a different way, he is passing on the judge’s lessons to the next generation and being a part of preserving the city’s history so Charlie, someday, could make the next round of decisions about places like Union Station should he choose to.

“What Dad baked into me was that … you have to be able to see things for what they can be. Right? Not just what they currently are,” Charles said. “So, I want to be a part of making this city the best it can be, not because it’s the town that’s raising Charlie, but because it’s the town that’s raising 10,000 other kids. So, I want there to be more opportunities for families, for those kids — whether it’s trains or more amenities or more parks and recreation amenities or something as simple as better streets to travel on. That’s what Dad was all about, building an infrastructure, literally and figuratively, that promotes community.”

•

The day before that car ride, the City Council voted to ensure a contract for the first phase of the Union Station stabilization effort — one that will be funded thanks to a $600,000 grant, private donations, and contributions from the city and county governments — will be approved at the board’s next meeting as part of its consent agenda.

But former Downtown Goldsboro Development Corporation Executive Director Julie Metz, the woman who secured the grant and has done much of the legwork to ensure the Saving Union Station group has been successful, would tell you there is still plenty of work to be done to see the judge’s dream of a revitalized Union Station come to fruition.

And because the late Gaylor was a man she counted among her most trusted friends — because she has heard him tell hundreds of stories and watched him, on countless occasions, pass on the city’s history in hopes it would secure its future, she felt strongly that future donors to the effort he helped champion could contribute in his memory.

So, after getting his family’s blessing, she drafted a letter that will soon be delivered to members of the many organizations the judge gave his time and energy to throughout the years.

“Let’s do this together, for Charlie,” it reads. “A person who always had his heart and eyes on the past and the future.”

His son believes his father, even in death, would have wanted to be a part of what he always dreamed would be one of Goldsboro’s greatest success stories.

And even though in body, he is gone, Charles believes the judge will be smiling down when his son — his namesake — signs the stabilization contract with T.A. Loving Company later this month.

“I hate that he’s not going to be here to see it. I hate that part. But I know he’s left his mark, and he will continue to,” Charles said. “You know, obviously I wish that he was going to be there. I wish that things could have played out any number of other ways. But above all, I’m glad that it’s happening. It’s gonna be, that’s gonna be, a special, special moment.”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Jan. 4, 2025

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!