Hidden in plain sight

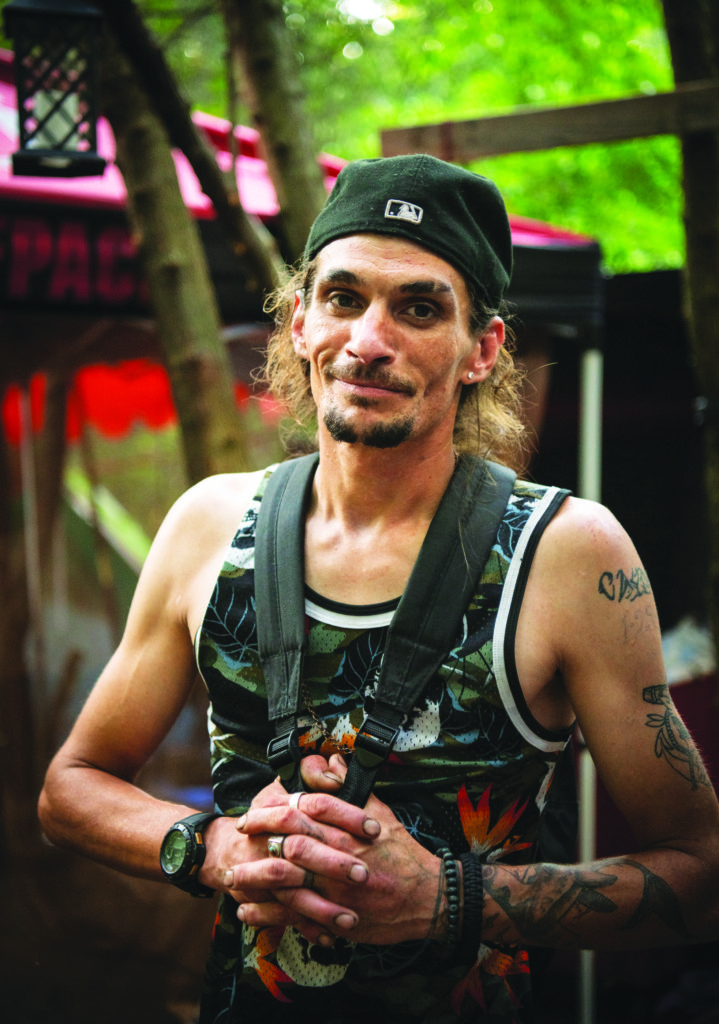

His hands clinching the straps of the black backpack secured to his shoulders, Chris Watson looks at the ground.

He doesn’t seem to notice that mosquitos have landed on his left shoulder and right forearm.

He doesn’t seem outwardly bothered by the July heat.

Despite what some might consider extreme conditions, he feels connected to this place — the collection of camp sites nestled a half a mile beyond the tree line off Royall Avenue.

He feels protected here.

He considers himself a survivor — of the many storms, scorching summer days, and snow-filled nights he has endured on these grounds.

But he is also keenly aware that the men and women living in Goldsboro’s Tent City need help.

So, his eyes focus on the ground as he ponders the perfect way to articulate his story — or why some 30 people have claimed these woods as their own.

He only looks up when the silence is broken by a frenzied whine of cicadas and the crack of boots meeting sticks and leaves.

“If you’re out here, you’re out here for a reason,” he says. “You’re either lost in the sauce or you got mixed up and turned the wrong way. Maybe you can’t put that needle down. Maybe you can’t let go. If you don’t have that drive — that, ‘I’m so sick of this. I’m tired of being hungry. I can’t take this heat.’ — it’s not gonna happen.”

His story, like so many of those unwrapped by Tent City residents that July evening, includes loss, tragedy, and addiction.

It’s the story of a “military brat” from a fairly typical American family who began to spiral.

“How did I end up in Tent City?” Chris said. “Dad didn’t like me stealing all his money out of the safe or putting my little sister in jeopardy by exposing her to the life that goes along with crack addiction.”

It’s the story of a father being alienated from his son.

“My son, who now calls me Chris,” he said. “He looked at me with disgust and told me, ‘You don’t have the right to ask me why I’m calling you Chris.’”

It’s the story of getting sober only to make “that one bad decision” that led to relapse.

“When I was in Wilmington, I stayed clean for almost 90 days,” Chris said. “And then, I came back to Goldsboro and went to my ex’s place. It was, of course, the worst mistake. Deep down, I probably knew, ‘If I go there, I’m gonna get high.’”

And it’s the story of watching a loved one’s life end at the hands of their addiction.

“I lost the person I was going to marry. She did nine bags of heroin after I fell asleep,” Chris said. “I passed out right there by the bed. All I remember was that beautiful girl. Her name was Rachel. She was right there. I could reach up and she was right there in that bed. … The next morning … I had to watch them put her in a bag. There was no warmth and life and love anymore. It was gone.”

After a few hours in Tent City, it becomes clear that Chris’ story could have belonged to most of the homeless population that resides in those woods.

Every one of them admitted to being an addict.

Several said they had mental health issues — from “social anxieties” to depression.

They understand the community’s concerns about the needles, the garbage, the piles of clothes, the broken furniture, and the shopping carts that line the paths that connect the many sites hidden behind the wood line.

Deep down, they know they don’t really belong there — that they need an intervention.

But they also know that the Goldsboro Police Department is limited in what it can do in response to what is, at the very least, trespassing.

They know that organizations will be there to donate water and food — even nights at local hotels when the weather is particularly extreme.

And they also have trust issues they say contribute to their reluctance to enter certain rehabilitation programs.

Solving the local homelessness and addiction crises, they would tell you, is an individual by individual, day by day effort.

Kellie Floars, the founder of Tommy’s Foundation — an organization in Wayne County that consistently serves the Tent City population — agrees.

“Every person is different. Every recovery journey is different,” she said. “Dealing with the addiction and dealing with the mental health aspects — plus their background and all the baggage that comes with them — it’s like a bag of cords that you’re trying to straighten out. But while you’re doing that, you have to love them. You have to be ready to answer that phone every time it rings.”

PHOTO BY CASEY MOZINGO

Michael Wheaton walks along the railroad tracks that separate Royall Avenue from the wood line.

It’s after 9 p.m. and the sun had set on the December day hours earlier.

According to witnesses interviewed by investigators from the Goldsboro Police Department, he doesn’t seem to notice that a Norfolk Southern Railroad train is barreling toward him.

He doesn’t respond to the sound of an air horn blowing again and again.

When he finally looks up, he is, in an instant, struck and killed.

City residents had been talking about Tent City for years.

They lamented the sight of garbage, piles of clothes, broken furniture, and shopping carts seemingly discarded just outside the encampment’s entrance and down the street.

Employees at nearby Target, Walmart, and the Wash House complained about shoplifting and heroin use in bathrooms.

Other businessowners were angry about the homeless hooking up to the faucets behind their establishments to bathe.

But whenever the Goldsboro police would take action in Tent City, officers were criticized for “targeting” the homeless.

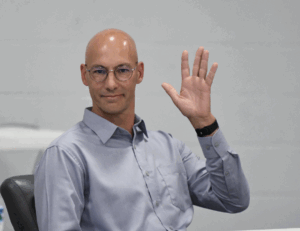

“A few years ago, the property owners signed (trespassing agreements) and wanted them off the property. So, we went in there in a first wave and warned all the homeless. We told them, you have 24 hours to get off the property or we’re going to come back and charge you,” Goldsboro Police Chief Mike West said. “Some left, some didn’t. The ones who didn’t were charged. We’re trying to clean up the property. We’re trying to get them off the property.”

In doing their job, however, the chief said the GPD created a perception problem for the city.

“So, the Salvation Army got wind of it at the time, and they became outspoken in the public saying that we went in there and applied a law enforcement solution to a problem that didn’t require law enforcement,” West said. “It was a PR nightmare for some of the city leaders. It didn’t look good. So, we backed off.”

But when Wheaton was killed on those tracks — and crime numbers in and around Tent City started to spike — some in the community, again, began demanding a resolution.

Police, however, ran into another roadblock.

On one occasion, they seized a large quantity of opioids from the woods and asked District Attorney Matthew Delbridge how to proceed.

“The information I got back from the D.A.’s office is that they weren’t willing to prosecute because we violated a search (protocol). We think, we’re in Tent City walking around and see dope and stuff. It’s in the open,” West said. “But, aha, it’s not in the open. It’s in Tent City. They have a certain expectation of privacy. We should have gotten a search warrant. That’s the information we were getting back.”

Fast-forward to the present.

Businessowners in the shopping center across the street from Tent City — and as far away as the YMCA — are growing increasingly concerned. Some residents are starting to avoid the area altogether.

After years of neglect, that particular section of Royall Avenue is, to put it mildly, unsightly.

“They have pretty much taken over that area to the point where businesses looking to come to Goldsboro to set up will ride through and it looks like a dump. I wouldn’t open a business up on Royall Avenue or Spence Avenue,” West said. “Then, a lot of property owners are like, ‘Hey police. What are you gonna do?’ Right or wrong, we say, ‘We tried to do something. We weren’t allowed to pursue it. And now, I’ve got bigger fish to fry. Let’s let these organizations try to work it out.”

And while he agrees that “the answer to homelessness is not jail” and knows that Tommy’s Foundation has shown a commitment to doing all it can to help those struggling with addiction, the “real” results have not come in the nearly five years since the Salvation Army blew the whistle on his officers’ attempt to clear out Tent City.

“I’ve heard a lot of talk, but I have not seen anything yet. There’s nothing,” West said. “So, I would love nothing more than to get staffed up and make that a priority because, again, my concern is not just for the people who live in the area. I’m also concerned for the businesses that want to come to that area. Goldsboro and Wayne County right now has got an opportunity to grow, and if we don’t play our cards right, we’re going to squander this away.”

But something has happened in that time.

“Calls for service in the Tent City or in the area related to Tent City is up 34 percent so far this year compared to all of 2022. 2022 was over 50 percent higher than 2021. Calls for service has steadily increased in Tent City and the area since 2021,” West said in a statement provided to New Old North by city public information officer LaToya Henry. “Some specific incidents or crimes that are on the rise are theft, assault, possession of stolen property and robbery. Overdoses are becoming more frequent and have increased already over the previous year. … According to the data, activity in and around Tent City over the past three years has become more criminal in nature and more violent.”

And now, as the controversial issue again comes to the fore, the GPD is facing a staffing crisis, limiting its ability to do the work it would take to make progress.

But should city leaders direct police to make strides beyond the wood line off Royall Avenue, Delbridge vowed to be a part of that solution.

His office, he said, is not against pursuing charges against those who are breaking the law in Tent City. He just wants to ensure the charges that are made can lead to viable court cases.

“It was never that we weren’t going to prosecute,” Delbridge said. “It was unclear whether these people had been properly informed of no trespassing, or if they were given required notice to vacate.”

The situation becomes more complicated when navigating search and seizure laws.

“Some jurisdictions consider a tent a home,” Delbridge said.

The district attorney said he and West have spoken recently about the Tent City concerns.

“We both understand that there is a problem,” he said. “We will move forward together.”

He added that he will consult with legal experts from the N.C. Conference of District Attorneys for advice on the best way to accomplish that.

PHOTO BY CASEY MOZINGO

Gordon Cole moves swiftly as he navigates the paths that connect the different sections of the neighborhood of sorts located beyond the wood line.

And when he gets to his campsite, located at the bottom of a hill in what is referred to as “Old Tent City,” he extends his arms — inviting those who have come to see the encampment for themselves to look at how clean and organized his home is.

“I don’t really live like the rest of them. Down here, we’ve got nice tents. We don’t sleep under tarps like some of the ones up there are doing,” he says. “And I don’t go out there and panhandle. I work. I just happen to live here.”

When he isn’t completing handyman or light construction jobs around the city, he fixes bikes at his campsite.

“Everybody that’s got a bike out here got it from me,” he says.

And like Chris and so many of the others who unwrapped their stories that July evening, Gordon found himself at Tent City as a result of loss, tragedy and addiction.

It’s the story of a brother who lost his sister, his best friend, to cancer.

“She was everything to me,” Gordon said. “My mom was a single mom and my sister raised me.”

It’s the story of making decisions that have destroyed relationships.

“Down here, all that don’t happen to me,” he said. “Down here, I have some control.”

It’s the story of making “bad decisions” and ending up in jail.

“Addiction is real. People might not think it’s real, but it’s real,” Gordon said. “So, sometimes, that addiction leads you to do things. Out here, there are certain things you have to do to survive.”

And it’s the story of watching a friend’s life end at the hands of their addiction. “(The young man who was killed by the train) was on drugs, but he also had very bad mental issues. He used to live with me,” Gordon said. “His real problem wasn’t the fact that he was a drug addict. His real problems were what led to him becoming a drug addict — the way he was raised.”

PHOTO BY CASEY MOZINGO

Kellie is stationed in a lot across the street from Tent City’s unofficial entrance. It’s Tuesday evening and that means a cadre of volunteers from Tommy’s Foundation are alongside her — waiting for the homeless to emerge from the woods.

In an instant, the sky grays and the wind begins to whip the tops of the tree line.

A downpour ensues.

Kellie is not deterred.

She and her team are going to make sure every one of the hungry walks away with some food — and perhaps, hope.

Solving the homelessness and addiction crises in Goldsboro is a 24/7 affair, she said.

You never know when someone is going to hit rock bottom — when they are, at last, ready to change their life.

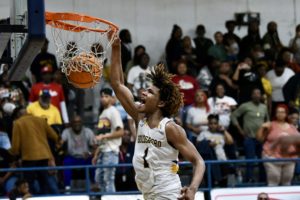

Nobody understands that more than Steven Pulley.

“Addiction is a battle every day inside your mind,” he said.

His story is very similar to those of Chris and Gordon and so many of the others who live, or have lived, in Tent City.

It’s the story of a Walmart manager who “had someone very close to me pass away.”

“My family didn’t really have much to do with me at the time,” he said. “So, I felt alone, and I took it hard.”

It’s the story of beginning to use drugs, losing his job and going to jail.

It’s the story of the toll crystal meth takes on a body and mind.

“I was in bad shape,” Steven said. “I was spiraling.”

But his is also the story of a man who, once upon a time, lived in the woods and was saved by a local nonprofit — a man who was placed into a rehabilitation facility in Wilmington and has been clean and sober ever since.

“I just knew I had to leave that lifestyle behind me. I wanted to make my family proud of me again. And she, she saved my life,” Steven said, looking at Kellie. “A lot of homeless people and addicts, they think that nobody cares about them. But Kellie, she cares. And she can’t do it by herself. She’s the most beautiful person I’ve ever met, but she needs all the help she can get.”

Kellie hopes that one day, the community will come together to solve the dueling homelessness and addiction crises plaguing their city, state, and country.

Her dream is to open Tommy’s House, a safe haven where treatment and recovery become a reality for the residents of Tent City and beyond.

Chris, Gordon and Steven believe it could be a difference-maker.

“Tommy’s Foundation will do everything in their power, and they want to help. A lot of people in the woods are skeptical of anybody trying to help because it seems too good to be true. They’ve been let down their whole life,” Chris said. “They have mentally prepared themselves for failure. But Kellie is different. If she got the funding for (Tommy’s House) they would be the ones to help build it.”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Feb. 8, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!