Fighting for their lives

A 13-year-old was riding her bicycle when she came across a helpless bird.

“It was just a baby,” she said. “It was not quite ready to leave the nest, but it had.”

The teenager had always loved animals — and had, during her youth, taken care of ducks, geese, and cats — so she took it home.

“I raised it,” she said.

But decades ago, Emily Fein had no way of knowing that rescuing the “innocent” would, in many ways, come to define her — that she would spend her days bottle-feeding kittens and rehabilitating what many believed were “lost causes” so they would grow into adoptable pets.

She might not have expected that the home in Fremont she would settle into with her husband and children would also become a sanctuary — a product, she said, of a local animal shelter without the capacity to take in a fraction of what she characterized as an “out of control” feral cat population in her home county.

The thought of coming home from delivering her youngest daughter to find that someone had “dumped” three kittens in her driveway might not have been conceivable.

But when Cindy Clawford tears around a corner, jumps a baby gate, and launches herself into a play battle with one of the 14 felines Emily is currently fostering, she laughs.

“Well, this is my life,” she said. “I mean, it’s a big house so we’ve got room for it, but it’s a lot for one person. But who else is gonna do it?”

And if her fosters had, instead, ended up at the Wayne County Animal Shelter, the odds would be stacked against them, as in 2023 (that data is the most recent available), more than half of the cats that came into the facility were euthanized.

“They didn’t ask for any of this. They didn’t ask to be left in some parking lot or stuck under a house,” Emily said. “So, we have to do something. We domesticated these animals 40,000 years ago for our own benefit and we have to do something about it. It’s our problem. It won’t solve itself. It’s just trying to figure out where to start unraveling.”

•

It typically starts on social media.

Someone finds a kitten and does not want it to die but also does not have the capacity or desire to shelter it.

“I get tagged,” Emily said. “So, there’s a handful of us now that everyone knows are the cat people. We’re the go-to for animals that have no home or who have lost their home.”

After that, it comes down to who “has the room” to take the animal in.

That was how Arlo — who was busy scratching his way up an armchair as Emily told his story — ended up in Fremont.

“I got him when he was a day old with his three siblings. The mama had abandoned all four of them,” she said. “He was the only one who made it.”

And those victories accompanied by heartache are, Emily said, something she and others in the community who do the same work have to reconcile with constantly.

Because when she bottle-feeds a kitten that can barely open its eyes — or places another in one of the incubators her husband, Zak, built for her — there is always a risk they won’t make it.

“We just do the best we can,” Emily said. “And hope for the best.”

•

Last year, through her non-profit, Emily’s Foster House, Emily successfully rehabilitated and adopted out 38 kittens.

But it’s a difficult metric to celebrate when she thinks about the tens of thousands of cats still living in abandoned houses, the engine blocks of junk vehicles, homeless encampments, fields, and wooded areas across Wayne.

And to make matters worse, colonies of feral cats balloon in numbers too quickly to contain.

From what she has witnessed, this, she said, is how it happens.

First, someone gets “tired of an animal” and “dumps it somewhere.”

“You know, like the end of a dead-end road or in a field or something,” Emily said. “It’s not their problem anymore.”

And because many of those cats are not spayed or neutered, they begin to reproduce.

“For every cat that you see, there’s gonna be a dozen more that run away and hide whenever people come around,” she said. “It really is exponential. If you’ve ever seen the graphic with cat math, it is one cat — one pregnant mama cat — can be responsible for thousands of cats in her lifetime. And when, like a lot of these, you start having them at four months old, there’s no hope.”

Then, the rapidly expanding population of ferals becomes a community problem.

“We don’t need any more kittens. We don’t. They can spread some pretty terrible things,” Emily said. “In my case, it was ringworm. I definitely could have done without that. There’s been rabid cats found in Wayne County and if we don’t do anything, there’s just more possibility for that to keep happening.”

That, she said, puts everyone’s pets and children at risk.

“Some of these cats have terrible things that can transfer from cat to cat or cat to human,” Emily said. “I had ringworm in places one ought not to have ringworm. It was terrible. Now imagine your child getting it from playing at the park.”

And as a member of the Wayne County Animal Control Advisory Board, she knows firsthand that local officials are not doing anything to prevent that from happening.

“We don’t even have meetings anymore,” Emily said. “I don’t know why. I don’t know what to do.”

So, she and her fellow “go-to for animals” have tried to put a dent in the problem on their own — soliciting donations for a spay and neuter initiative that would, at the very least, stop the thousands of feral cats lurking across the county from breeding.

But ever since SNAP stopped coming here, even that has been challenging.

“There’s a lot of people willing to do the work. We’ve got a solid group of people that know how to work a trap and know what to do with that, but we’re currently driving to Safe Haven in Raleigh to fix these animals after we trap them,” Emily said. “So, we have to find a person that has the availability of picking up 10 crates of happy cats, sad cats, pissy cats, whatever and driving them to Raleigh, staying up there and waiting until they are all spayed or neutered, and then driving them back.”

It is not, she said, sustainable.

But one solution she has come up with might be.

“If the county could make some funding available to hire a veterinarian, it would take some pressure off the shelter,” Emily said. “They could take care of the animals in the shelters — their vaccines, medicine, whatever — and then, they could spay and neuter. If we could do something like that, it would be huge. We can’t afford to take a stray cat from off the streets and spend $300 to get it spayed. So, we need low-cost spay and neuter. That is the starting point for all of this.”

Otherwise, there is no end in sight for what she and others fear is a problem most people won’t even acknowledge until something tragic happens.

“There is a huge disconnect throughout the entire county,” she said. “But if something horrible happens — and it will — what are we going to do then?”

Her fear? Mass killing of “innocent” animals.

“I’m getting two of them tomorrow — two bottle-feeders that are about two weeks old. But the guy who found them at his workplace said everyone there that worked with him just wanted to kill them,” Emily said. “And because of the tragic conditions at the shelter, you have to kill little dogs and cats because you didn’t address this problem, and you can’t find them homes because people can’t be bothered.”

Note: Those who are interested in adopting a cat from the Wayne County Animal Shelter can find details about how to do so in this week’s Spectator section. Those who are interested in helping Emily can drop off donations — food, litter, toys, and monetary donations made out to “Emily’s Foster House” at Goldsboro Brew Works or GBW: The Filing Station.

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Feb. 22, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

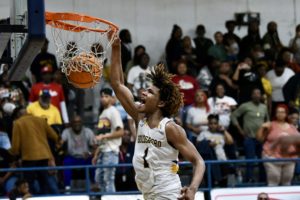

Final Four!