Edgewood relocation plan enrages parents

Deann Poirier turns to face both the chairman of the Wayne County Board of Education and its longest tenured member.

Her voice is trembling.

“Honestly, you cannot look me in the eye and say if you had a kid that was in this school, if these were your children, that you would think this is the right decision,” she said, almost in a whisper. “You just can’t. I know you have a budget, but this isn’t right.”

Craig Foucht and Chris West remain silent.

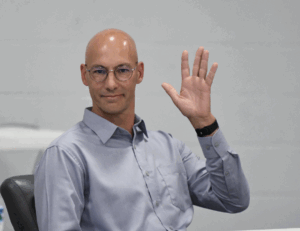

For Poirier, the decision unwrapped moments earlier by Wayne County Public Schools Superintendent Dr. Marc Whichard was, at once, shocking, devastating, and “wrong.”

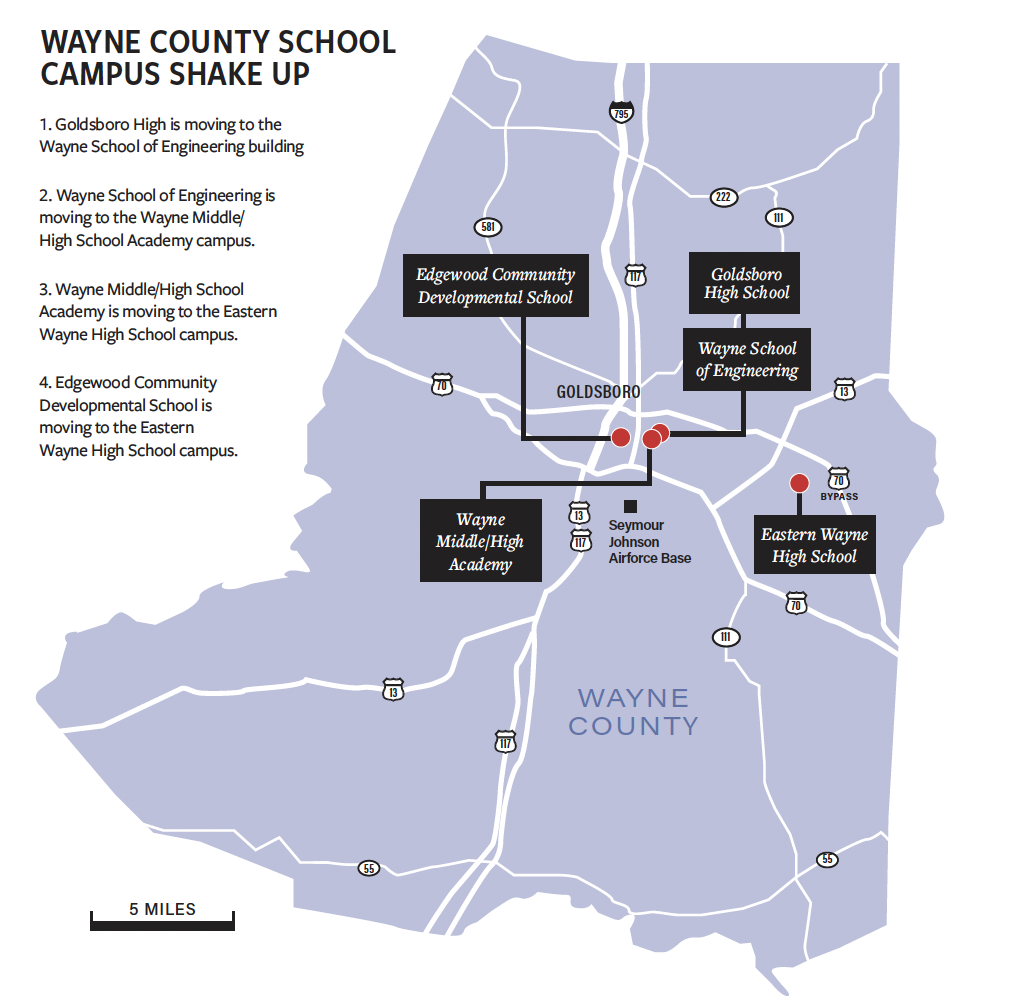

The Edgewood Community Developmental School student body was, come August, being moved to the Eastern Wayne High School campus.

And the “home” many have known for more than a decade would likely be sold as surplus after they’re gone.

“I almost want to say, ‘Pick on somebody else, please,’” Poirier said. “We have something that’s more precious than any amount of money. That is our beautiful, wonderful children. And this is their home.”

She knows that now, she is going to have to figure out a way to explain the transition to her daughter, Charlotte — an 18-year-old who was born with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, a condition characterized by short stature, moderate to severe intellectual disability, distinctive facial features, and eye abnormalities.

She wasn’t alone.

In fact, most of the metal folding chairs lined inside the Edgewood auditorium Tuesday evening were taken by teachers, staff, and family members of those who will soon be moving to Eastern Wayne as part of a unanimously-approved “facility utilization” strategy broached by Whichard at the School Board’s retreat in Ocracoke back in August and formalized earlier this month without any comments from members of the board.

Toya Williams, whose 17-year-old daughter, Angel, was born with autism and has been attending Edgewood since shortly after her third birthday, was among those taken aback both by what she feels was the lack of an opportunity for parents and school advocates to address the superintendent and the board before the decision to move the school was made and what she characterized as their lack of understanding of just how much such a significant change would impact the school’s students.

“I flipped out. (Whichard) doesn’t understand. If you move these kids, it’s going to be a disaster. The way my daughter is, when she gets mad, she breaks things,” she said. “When her routine is broken, she’ll destroy everything. She already put a hole in the wall. She ripped the seats out of my (car). Do they want to see pictures of what she’ll do?”

Lisa Hadley agreed, unwrapping what happened the last time her daughter was thrown off her routine.

“It got to the point where she would not go to school. It got to the point where she would not leave her bedroom. It took me two weeks to get this baby out of her room,” she said, before pausing to collect herself. “No more laughing. No more smiling. She didn’t want to do anything. Nothing. It took me a month after I got her out of her room to just get her to go outside and play.”

This is not the first time Edgewood has made headlines — nor is it the first time the Board of Education has come under fire for making changes to the school.

Back in 2019, the school faced potential closure, but thanks to then-board members Jennifer Strickland, Dr. Joe Democko, and the late Rick Pridgen, it was spared, although dozens of the student body’s youngest students were transferred to Meadow Lane Elementary School.

Then, in 2021, the board voted to require Edgewood’s sixth- through eighth-grade students to move to Greenwood Middle School.

But unlike what unfolded five and three years ago, respectively, this time around, the subject was, as one parent put it, “hidden” to “avoid a scene” at the board’s Feb. 5 meeting.

According to the agenda sent to members of the media as part of the district’s requirement to notify the press — and public — ahead of official meetings, there was no mention of Edgewood.

In fact, there was no specific mention of any of the four schools impacted by the decision formalized Feb. 5.

Instead, there was a line item called “Facility Utilization Plan.”

“The school board is trying to pull the wool over our eyes,” Hadley said.

The end of Edgewood as the community knows it has been in the works since at least late August when Whichard, at the board’s retreat in Ocracoke, said taking steps to properly utilize the space the school district currently has would take out of the Wayne County Board of Commissioners’ “arsenal” the argument that the school district should not ask for more funding for facilities until it maximizes use of what it already has.

“Don’t give me anymore, ‘We’re not using what we’ve got,’” he said at the meeting. “Here’s how we’re righting the ship.”

From potentially relocating Wayne School of Engineering and moving modular units onto Seymour Johnson Air Force Base to bussing Central Attendance Area students to the soon-to-be-completed Fremont Elementary School, the superintendent said all options were on the table and that in his perfect world, a facilities plan would be ready by Spring 2024.

“This is going to require a lot of, in some cases, soul searching in what we want to do and how we want to do it,” Whichard said. “We have a lot of property that can be better utilized. All it takes is a drawing board in terms of how we make those adjustments.”

The superintendent delivered earlier than he expected — and Edgewood is only one piece of what he characterized as a “puzzle.”

Wayne School of Engineering is now set to move to the campus currently occupied by the district’s alternative school, Wayne Middle/High Academy, which will, like Edgewood, relocate to Eastern Wayne.

But Whichard said Wayne Academy students would still be contained — separated from those attending class inside Eastern Wayne — because they will occupy the campuses “modular suites.”

And despite concerns shared with New Old North by nearly a dozen EWHS teachers about the presence of students who, in many cases, have been removed from traditional schools because of serious disciplinary offenses, WCPS has a solution.

According to five people who were in attendance during a meeting of the Wayne County Republican Party Feb. 12, Foucht announced the district planned to build “a fence” around the modular units that will house the Wayne Academy student body.

Whichard, during an interview Wednesday with New Old North, confirmed that the measure would, in fact, be implemented.

“We’re going to put up some fencing so the area is secure,” he said.

One of those who attended the GOP meeting said they were concerned about “how we’re going to look.”

“When he said that, I was in complete shock,” said the source, who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation from party officials. “I just can’t believe anyone thinks, ‘Hey, let’s build what looks like a prison to contain a bunch of kids who, let’s face it, people think are criminals.’ If these kids are so dangerous, why in the world are we putting them at Eastern Wayne? If I was a teacher at Eastern Wayne, I’d be looking for a job outside of the county immediately.”

During his sit-down with New Old North, Whichard said he understands that the relocations of Wayne Academy, Goldsboro High School, and Edgewood have created a stir in the community — that change is always met with some level of resistance.

But he also said that he has learned to “tune out the noise” so he can remain focused on the big picture — doing everything he can to fight for more funding from the Board of Commissioners to make WCPS the very best it can be.

And he said he was not surprised by the reaction of the parents he addressed at Edgewood Tuesday.

“I get it. I’m a parent. Every child is important to their parent, regardless of any special circumstances,” Whichard said. “I expected the overwhelming majority to be upset.”

But he also thinks he accomplished explaining the “why” — and reiterated that once the families see how much work has been and will be put into Eastern Wayne to ensure the smoothest transition possible, they will be more at ease with the relocation of the school.

“It’s got to be just right before we push a button on this to happen,” he said. “We’re looking at every single detail. This will not be rushed.”

Williams said she “wasn’t convinced” and vowed to fight the decision.

“This is all my daughter knows. She has been here since she was 3 years old. You want me to move her over there? That’s another change. That’s going to affect my household. I have two autistic kids. I’m already going through stuff,” she said. “This is a disaster. This is not no program. This is a school. This is a family. That’s what y’all don’t understand.”

And they also don’t understand just what it’s like to walk in the shoes of those who care for severely disabled children, she added.

“Our children, it’s more than a home to them. Our children are able to come here every day happy —not crying, not being picked on, talking to each other, playing with each other,” Williams said. “I don’t care how y’all spin it. … We know Edgewood is what it has to be for our kids. I just hope and pray y’all don’t wind up with a daughter or a grandchild … with a disability like this one day, because that’s the only way you’re going to understand. Sometimes, you have to go through it yourself. You can walk around these classrooms all day long, but you ain’t gonna get it until you’re there every day.”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Feb. 22, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!