City to begin ‘compassionate relocation’ of Tent City residents

Members of the Goldsboro Police Department have tried to address the city’s homelessness and addiction crises before.

But when, more than five years ago, they attempted to enforce trespass agreements and clear out the encampment known as “Tent City,” they faced backlash for what some non-profits and local residents considered a lack of compassion.

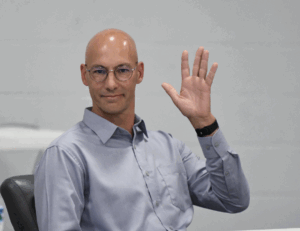

“The property owners wanted them off the property, so we went in there in a first wave and warned all the homeless. We told them, ‘You have 24 hours to get off the property or we’re going to come back and charge you,’” GPD Chief Mike West said. “Some left. Some didn’t. The ones who didn’t were charged.”

What lawmen didn’t know was that doing their jobs would put them at odds with some in the community — non-profits and residents who characterized the arrests as everything from “heartless” to “wrong.”

“The Salvation Army got wind of it at the time, and they became outspoken in the public saying that we went in there and applied a law enforcement solution to a problem that didn’t require law enforcement,” West said. “It was a PR nightmare for some of the city leaders. It didn’t look good, so we backed off.”

They also didn’t anticipate that the Wayne County District Attorney’s Office would decline to prosecute those they had arrested — like when, on one occasion, Goldsboro police seized a large quantity of opioids from the woods and asked District Attorney Matthew Delbridge how to proceed.

“The information I got back from the D.A.’s office is that they weren’t willing to prosecute because we violated a search (protocol). We think, we’re in Tent City walking around and see dope and stuff. It’s in the open,” West said. “But, ah-ha, it’s not in the open. It’s in Tent City. They have a certain expectation of privacy. We should have gotten a search warrant. That’s the information we were getting back.”

Between then and now, violent crime attributed to Goldsboro’s homeless population has been on the rise.

People have died — including a Tent City resident who was struck and killed by a train on New Year’s Eve 2021.

People have been shot — including a 33-year-old who took a bullet to the leg in November 2023 during an argument that unfolded beyond the tree line off Royall Avenue.

Businesses have been victimized — like when, over the years, dozens and dozens of items have gone missing from Target and Walmart, including, most recently, an electric bicycle allegedly stolen by a Tent City resident in September.

Drug overdoses and fires are becoming more common in city homeless encampments.

And as of a few months ago, the GPD reported that “in Tent City or in the area,” calls for service had increased more than 34% compared to 2022.

“Some specific incidents or crimes that are on the rise are theft, assault, possession of stolen property and robbery,” officials said. “We are seeing more drug-related calls and arrests as well. According to the data, activity in and around Tent City over the past three years has become more criminal in nature and more violent.”

Shoppers are finding used needles and trash in the parking lots of stores close to Tent City.

Locals have voiced concerns at City Council meetings — like the man who spoke to the board Monday about increasingly “aggressive” panhandlers who bang on cars and a business owner who said a “drug addict” nearly beat one of her employees to death.

All of those issues, West said, are compounded by his depleted ranks — a hot button issue that has led members of the council to consider increasing GPD salaries so the department can get “staffed up.”

But despite his staffing problem, Goldsboro’s police chief said the time has come to take action.

It will not happen overnight, and lawmen anticipate challenges along the way, but the GPD is beginning a months-long process that has been characterized as a “compassionate relocation” of the dozens of homeless residents currently living across Goldsboro and, primarily, Tent City, an encampment located just beyond the tree line behind the railroad tracks that line Royall Avenue.

West said officers are canvassing both Tent City in specific and Goldsboro in general to identify who — and how many — need an intervention before officers, in lockstep with local non-profits and city leaders, work toward an end goal of providing services that will render the sites unnecessary.

“We haven’t gotten any marching orders to do it. This is just something we have been needing to do for quite some time,” West said. “We were going to do it late last year, but we just, with staffing things and other things that came up, we got delayed.”

The first step — to “identify the homeless encampments, not just Tent City, but in the city, and once we do that, we’re going to get up with the property owners whether it be city property or other private property to see if they want to assist us with trespass agreements” — is already happening.

Currently, three of the five owners of property that currently houses Tent City residents have signed on.

“We have to start somewhere. Right now, it’s, ‘What locations do we need to concentrate on? Where is everybody located at?’ Then, let’s get those trespass agreements,” West said. “That’s kind of the first wave.”

And once officers know just how many people they are dealing with, non-profits will be brought on board.

“We want to work with them to say, ‘OK. On this date come with us. We’re going to go through the camps, and you can tell them what resources are available,’” West said. “It’s gonna be a very long process, but it’s also going to be a compassionate process. It’s not going to be to just go out there and run them off the property. We are going to identify them. Then, it’s, ‘You’re trespassing. These resources are available to you.’”

But the chief understands that one of the major hurdles to overcome is the complacency of those choosing to live in the woods — that some people in Tent City and other city encampments have no interest in joining mainstream society.

Still, doing nothing is no longer an option.

“Crime is being involved more out there. We know there is more violent crime out there — more victims,” he said. “It’s time to do something.”

Only now, he will be instructing his officers to do it with more consciousness of the sensitivity of the situation — and the community’s divide on just how to rectify it.

“We understand this is the wintertime and it’s cold. Now might not be the time to be moving people off of an area that they feel comfortable in and where they have their resources set up,” West said. “But we’ve got to start it at some point. It’s gotten out of hand. So, that’s what we’re going to do. Again, it’s not a run through and kick everybody out. It’s a run through and let’s see if we can get you some help, because we know they need it. But the businesses around these camps and the citizens have rights, too. So, yes, we’re going to get to work.”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Feb. 8, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!