Storm’s a comin’

Back in early 2022, North Carolina Treasurer Dale Folwell excoriated Goldsboro leaders for the city’s repeated inability to fulfill its financial reporting obligations in a timely manner — and charged then-State Auditor Beth Wood with taking a deep dive into how business was being conducted inside City Hall.

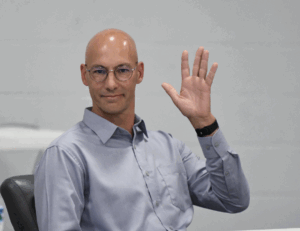

Nearly two years later, the preliminary findings were sent, via email, to City Manager Tim Salmon — a series of claims that seemingly substantiate Folwell’s fear that something wasn’t adding up in the Wayne County seat.

From former City Council members using tax dollars to fund expensive trips to Los Angeles, California and San Antonio, Texas and Water Department employees wiping away thousands of dollars in debt accrued by family members and city leaders to Salmon breaking city protocol and ignoring his department heads when they questioned what they believed to be “potentially fraudulent” use of federal COVID-19 funds, the authors of the report highlighted lack of oversight, shoddy leadership, and numerous actions that threaten to undermine the public’s confidence in its local government.

The following stories came to fruition because a confidential state source decided to ensure the confidential report was not kept in the dark.

“What has been allowed to go on for years is absolutley crazy and people have the right to know,” they said. “That’s the only way you’re ever going to change Goldsboro for the better.”

Editor’s Note: The preliminary report is just that and the city has been given until Jan. 26 to challenge the findings revealed by auditors if local leaders believe — and can prove with documentation — that any of the facts uncovered by the state are wrong.

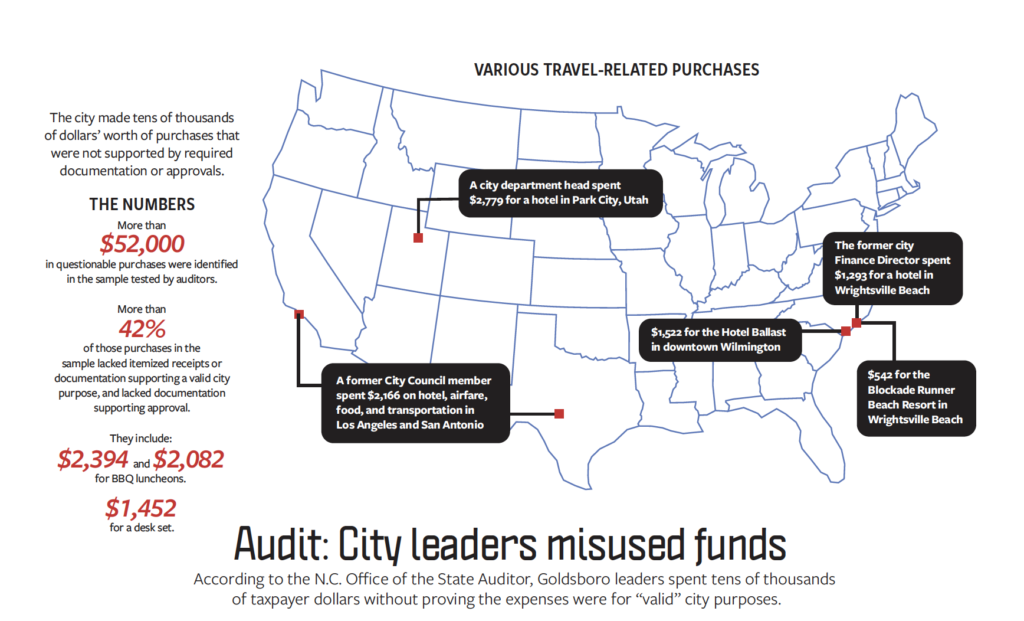

One former member of the Goldsboro City Council took a trip to Los Angeles, California and San Antonio, Texas.

A current city department head spent nearly $3,000 for a hotel in Park City, Utah.

The former Finance Department director went to Wrightsville Beach.

And thousands of dollars were spent on everything from a nearly-$1,500 desk set and a trip to a North Carolina beach resort to several barbecue luncheons that cost north of $2,000 apiece.

According to the preliminary findings outlined by the State Auditor’s Office in a report sent to City Hall Jan. 12, Salmon and Finance Director Catherine Gwynn — and their predecessors Scott Stevens and Kaye Scott — turned a blind eye to tens of thousands of dollars in purchases charged to city procurement cards that were not justified by required supporting documentation or approvals.

The audit, initiated in March 2022 after Folewell called for it amid Goldsboro’s inability to hit financial reporting deadlines, is nearing its completion, but the state tipped of city leaders about its findings to allow for an official response it has asked to receive by Jan. 26.

That email — and the “issues” detailed in a series of documents attached to it — were obtained by New Old North through a confidential source.

Here is what auditors found after analyzing a sample of 194 of the 32,000 “P-Card” purchases made from July 2017 to June 2021:

• Auditors tested 194 purchases totaling $100,733 and determined that 81 of them — 42 percent — lacked itemized receipts, documentation to support “a valid City purpose,” or documentation of approval.

• The total amount of money spent on those scrutinized purchases was $52,211.

• Specifically, 53 purchases that “lacked documentation to support a valid City purpose” were related to travel, including:

- $2,166 spent on a hotel, airfare, food, and transportation by an unidentified former City Council member in Los Angeles, California and San Antonio, Texas.

- $2,779 spent on a hotel in Park City, Utah by an unidentified current city department head.

- $1,293 spent on a hotel in Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina by former Finance Director Kaye Scott.

• More than a dozen purchases lacked “itemized receipts, documentation supporting a valid City purpose, and lacked documentation supporting approval,” including:

- $542 for a stay at the Blockade Runner Beach Resort in Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina.

- $1,522 for a stay at the Hotel Ballast in downtown Wilmington, North Carolina.

- $2,082 for a BBQ luncheon.

The report placed blame squarely on “city management” and its lack of oversight over purchases made with Goldsboro credit cards that saw taxpayers foot bills for everything from extravagant travel to expensive meals.

And auditors warned city leaders that more misuse of funds is possible.

“Since over $52,000 of purchases were not supported by documentation or required approval, there is an increased risk that the City paid for purchases that did not have a valid City purpose,” the report reads. “The P-Card purchases identified above were only those identified in the sample and may not include all that exist in the entire population.”

That “entire population” includes 4.6 million tax dollars.

It is unclear whether members of the current City Council will call for a thorough analysis of all 32,000 purchases made with Goldsboro credit cards between July 2017 and June 2021 now that the state has identified misspending in nearly 50 percent of its sample.

But the State Auditor’s Office recommended that leaders consider pursuing “recovery” of the tax dollars used for the purchases that lacked required documentation and/or approval and revoking P-Card privileges of any current employees tied to them.

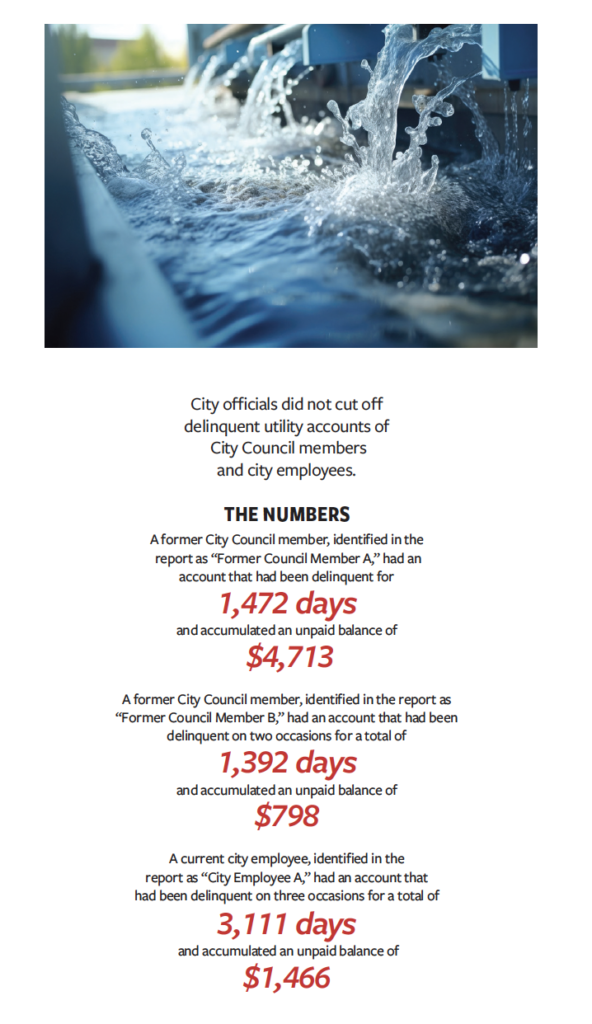

In 2020, while Salmon was recommending water rate increases for Goldsboro residents, he knew that a member of the City Council had not paid their water bill in more than four years — and, despite a debt of more than $4,700, had not had their utility services cut off.

But the elected official — who was identified only as “Former Council Member A” in a preliminary report drafted by the North Carolina State Auditor’s Office — was not the only member of the board who enjoyed running water despite a massive unpaid balance.

A second person, identified as “Former Council Member B,” was delinquent on two separate occasions without penalty — for a total of 1,392 days that resulted in an accumulated unpaid balance of $798.

And a current city employee was not cut off, “even though the account was delinquent on three separate occasions for a total of 3,111 days” and carried a $1,466 debt.

“In each instance, the city should have cut off City Employee A’s account for nonpayment,” the report reads. “However, the city allowed the account to remain open and continue to accrue usage for a total of more than eight years and six months.”

The findings, which state officials blamed on “inaction from city leadership,” were one of six impeachments discovered during the “thorough audit” Folwell instructed the State Auditor’s Office to perform in January 2022 amid concerns that the city’s consistent failure to meet financial reporting obligations might be indicative of finances that “might be in disarray and therefore vulnerable to mismanagement or misappropriation.”

The six issues sent to City Hall by Performance Audit Manager Brandon James via email Friday seem to validate Folwell’s fears.

And in the case of Goldsboro leaders giving council members grace not extended to the general public, officials believe they “risked giving the appearance of unequal treatment eroding the public’s confidence.”

“Equal treatment by the government is a key responsibility for government leaders. Standards from the United States Government Accountability Office state that those entrusted with public resources are responsible for providing service to the public effectively, efficiently, economically, ethically, and equitably,” the report reads.

The preferential treatment extended by the Water Department to council members and city employees did not begin on the watches of Salmon and Gwynn.

The city “should have cut off Former Council Member A’s account for nonpayment” in October 2016 and Former Council Member B and City Employee A should have lost service numerous times had they been held to the same standard as ordinary residents.

But according to the state, more than a year-and-a-half of Former Council Member B’s — and more than a year of the City Employee A’s — nonpayment occurred under the current city manager’s watch.

“The City Manager and Finance Director inherited all three long-standing delinquent accounts when they began employment with the City in 2019,” the report reads. “However, they did not correct the actions of their predecessors. Consequently, the utility accounts continued to accrue usage for another 17-18 months.”

Salmon and Gwynn were not the only ones blamed.

The state also alleges that former Finance Director Kaye Scott granted “an informal, verbal payment arrangement to Former Council Member A” in lieu of cutting off their water service — a deal “not offered or made available to other utility customers” that, like the inaction of Salmon and Gwynn when they took the reins in 2019, ran the risk of alienating city residents.

“Unequal treatment could prevent the proper operation of democratic government by threatening the public’s confidence,” the report reads. “For example, the City Code of Ethics states: The proper operation of democratic government requires that public officials and employees by independent, impartial and responsible to the people … that public office not be used for personal gain, and that the public have confidence in the integrity of its government.”

Despite the fact that Goldsboro was designated a “distressed utility” under the state’s Viable Utility Program in 2021 and Salmon has repeatedly encouraged members of the City Council to increase water and sewer rates since 2020, the city “wasted approximately 2.2 million gallons of the City’s water and sewer resources over three years by distributing water without collecting payments,” according to preliminary findings from the state investigation completed after Folwell delivered a scathing review of city leaders for failing to meet its audit requirements — which he characterized as a “basic but critical oversight function.”

“It is troubling that the state’s 30th largest city, the county seat and home to Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, no less, has been unable to get its act together,” Folwell said in January 2022, before instructing then-State Auditor Beth Wood to conduct a “thorough audit” of Goldsboro’s practices. “Audits are necessary to assess financial well-being, to ensure bills are being paid and money is not missing.”

According to the report, money that should have made its way into local coffers did not. Specifically, from 2019 to 2022, Goldsboro left at least $52,914 on the table and “risked setting a tone that not paying utility bills was acceptable.”

From untimely cut-off of delinquent accounts and illegal reconnection of disconnected services to city employees crediting delinquent accounts inconsistently and without just cause, auditors bemoaned the fact that a municipality with a utility system with “urgent needs for increased revenue and investment” would leave so much money on the table while, at the same time, increasing bills for paying customers.

“In fact, minutes from City Council meetings show frequent discussions on the poor fiscal health of the City’s utility system,” the report reads.

And auditors blamed leaders inside City Hall for failing to develop “written policies and procedures to govern utility operations.”

Here is, specifically, what they found:

• Auditors reviewed the detailed account balance history for 19 accounts that were delinquent from July 1, 2019, to June 30, 2022, and found that the Utility Department did not cut off the 19 accounts until between 34 and 817 days after what should have been the cut-off date. From that date until their eventual cutoff, those customers used approximately 2.19 million gallons of water and sewer services without paying.

• Auditors found that the Utility Department did not detect in a timely manner, or, in some cases, at all, the illegal reconnection of utility services on accounts that had been cut off. They reviewed 167 accounts that were delinquent between October 2020 and November 2022 for nonpayment and determined that 9 percent of the customers illegally reconnected their service and resumed usage.

• Auditors reviewed the account billing history for 36 accounts that were “delinquent and/or in the name of a City employee or elected official” from July 2019 to June 2022. They found 24 balance credits made to those accounts — and that the city could not justify that they were necessary, calculated correctly, or approved by the unidentified “Utility Customer Service Supervisor.” As far as how much money that cost the city, the state was unable to make a determination. “Since the Utility Department did not have supporting documentation … auditors could not determine how many gallons of water and sewer usage were unpaid,” the report reads.

• Auditors determined that the city failed to collect at least $24,537 in water and sewer services provided to delinquent accounts with untimely disconnections.

• Auditors determined that the city failed to collect $1,012 in stolen water and sewer services.

• Auditors determined that the city failed to collect $40,520 because of “unsupported balance credits.”

It is unclear how the city intends to resolve the issues discovered by the state, but the authors of the report made several recommendations including pursuing collection of utility account balances owed due to nonpayment, illegal reconnection of service, and unsupported balance credits.

They also urged Goldsboro leaders to refer those who illegally reconnected their utility services to law enforcement and to develop and implement written policies and procedures that would allow for oversight and ensure nobody receives preferential treatment because of their status as an elected official or their relationship to a city employee.

Nearly $4,000 to repair a non-profit director’s personal vehicle, a Lexus RX350.

Another $3,500 for a down payment on that same non-profit director’s new Acura MDX.

More than $9,500 for rent for two LLCs and “additional staffing and worked performed” for a small business that was not accompanied by required documentation.

And that only represents what state auditors found among a fraction of the recipients — seven non-profits and small businesses — of Coronavirus Relief Funds they received from Goldsboro coffers.

According to the preliminary findings, Salmon overrode objections from department heads, dismissed grant agreement requirements, and brushed aside the city’s “existing financial procedures,” leading to misappropriation of more than $21,000 in federal funds.

As a result, state officials are recommending the North Carolina Pandemic Recovery Office review all payments to non-profits and small business — $248,996 worth — and pay back all “expenses determined by NCPRO to be not allowable or lacking key documentation.”

Here is what is in the report:

• Auditors tested the city’s disbursements to seven non-profits and small businesses that received a total of $92,500 from November 2020 to April 2021 and found that nearly a quarter of the money spent — 23 percent — was used for expenses that were “not necessary, not incurred due to the pandemic, and not adequately documented.”

• Salmon and his then-assistant overrode the objections of department heads regarding payments to Three in One Family Center — the non-profit run by the person who spent $4,000 to repair their Lexus and $3,000 for a down payment on a new Acura — they characterized as “overreach,” “iffy,” “wasteful,” and “potentially fraudulent.” One also told Salmon the purchases “looks like a scam.”

• When asked why he approved the above, Salmon told auditors the city was in “a state of emergency” and his job was to “slow the spread of the virus and potentially save lives.” He said he believed Three in One Family Center’s director was doing that. “There’s no telling how many lives he saved. Maybe he saved zero, maybe he saved many,” Salmon said.

• When asked why he approved the above, Salmon’s then-assistant told auditors the leadership team’s mindset “was to get this process (paid) quickly,” and that he and Salmon “felt like we were being creative.”

• When asked why he ignored existing city procedures, Salmon said, “I don’t know. I guess service.” When Salmon’s then-assistant was asked the same question, he responded, “I don’t know. That’s a good question.”

• Auditors said the city violated federal law and guidelines by failing to “distribute funds to recipients for qualifying expenses that were necessary, incurred due to the pandemic, and adequately documented” — that as a result, $21,346 was “wasted.”

It is unclear whether the city is on the hook for the $21,346 the state says was misspent, but auditors did recommend that Goldsboro should “immediately recoup all expenses” that have been — and could be should the city follow auditors’ recommendation that it have the NCPRO investigate all 248,996 dollars spent — determined to not be allowable or lacking key documentation.

But assuming the City Council takes the finding seriously and follows the state’s call to action, the board would “provide regular oversight of city leaders and management to ensure that legal requirements are followed, and financial resources are safeguarded.”

State auditors found the city could not account for 145 of the 575 city-owned vehicles listed in its inventory — a black-eye the state said represented yet another example of failure by leaders inside City Hall.

The “issue,” they said, increased the risk of “eroding public trust” in its local government by demonstrating how the city failed to “safeguard” taxpayer-funded property.

Here’s what we know:

Auditors obtained an inventory of 575 city-owned vehicles from the fleet management system so they could review the list for inconsistent record-keeping.

They tested 334 of them that raised red flags — some, because they existed in the Department of Motor Vehicles database but not the city’s records, and vice versa.

Of those 334, the city “could not account for, explain, or provide documentation supporting the status or location” of 43 percent of them. Among the unaccounted-for vehicles include 122 cars and trucks, 20 cargo and utility trailers, and three commercial lawnmowers worth north of $117,000.

According to the state, city officials could not account for the vehicles because “the City’s Fleet Maintenance Division did not follow City policy that required adequate accounting procedures and records for fixed assets.

And to make matters worse, an unidentified “Fleet Maintenance Superintendent” admitted to auditors that the city did not perform annual inventory counts of city-owned vehicles.

When asked why there was a discrepancy between a July 25, 2022, inventory report and a copy of the entire fleet management system database provided to the state less than a month later, the city’s Information Technology director told auditors that the Fleet Maintenance Division had been “improperly deleting records when vehicles were sold or disposed of instead of archiving them.”

Shortly thereafter, the person identified in the report as the “Fleet Maintenance Superintendent” could not explain “why or who was responsible.”

But the missing vehicles were not the only issue discovered during the audit.

The state also found that “vehicle records were inaccurate,” with some city assets listed in the database with incorrect Vehicle Identification Numbers and missing license plate numbers and others that had been “misclassified as surplus.”

“Since the City was unable to account for 145 City-owned vehicles, the City did not ensure that City property was safeguarded,” the report reads. “Since the vehicles could not be accounted for and no documentation could be provided that supported the vehicles’ status and location, it would be difficult for the City to detect fraud, waste, or abuse related to the property.”

And it also risked eroding public trust.

“The City not keeping track of and accounting for City-owned vehicles risks eroding the public’s trust in the City’s financial administration and stewardship of public resources,” the report reads.

Auditors recommended Goldsboro leaders “immediately” conduct an “independent and complete” physical inventory count of all vehicles and equipment — and that it repeat the process “on at least an annual basis.

A current Goldsboro employee allegedly used their position to credit their mother’s utility account nearly a dozen times between Jan. 30, 2019, and March 30, 2022, to reduce her water bill by more than $400 — an alleged crime state officials blame on inaction from city leaders.

The claim of the employee’s ability to offer “preferential treatment” and receive “financial gain without detection” was the last of six “issues” discovered during the “thorough audit” Folwell instructed the State Auditor’s Office to perform in January 2022.

According to the document, the employee, who was not identified, should only have been authorized to credit utility account balances with “proper support and managerial approval.” But when asked by auditors to unwrap Goldsboro’s process, “the Utility Customer Service Manager and Supervisor” said the city had an “informal practice” that allowed employees to credit accounts when they had “unusually high water consumption” — but only after documentation was provided that proved the cause of the high consumption, like a leak, had been resolved.

But in the case of the employee’s mother, city leaders were unable to provide “any documentation to support balance credits” and a person identified only as the “Utility Customer Service Manager” admitted to auditors that “the credits should not have occurred.”

The city employee, though, said their mother had “a series of plumbing issues” that led to the necessity for balance credits and that the department manager verbally agreed to the 11 credits. That claim was denied by the manager who said they were “unaware” the transactions had occurred.

The finding, like several others noted in the preliminary report, prompted state officials to question managerial practices inside City Hall.

“The City employee was able to abuse their position without detection because the Utility Department did not monitor to ensure balance credits were properly supported and approved,” the report reads. “Employees were able to make balance credits to any account, including their own, without any oversight by management.”

It is unclear whether or not the employee will be terminated for what the state said was, at the very least, a violation of the City Code of Ethics. Criminal charges could, theoretically, be on the table as well should the city determine crediting a family member’s water account without documentation qualifies as theft.

But the state recommended the city at least consider taking some action — both against the employee and by putting controls in place to ensure the same behavior is not repeated in the future.

“The City of Goldsboro should consider disciplinary action against the City employee that abused their position by making unsupported balance credits to their mother’s utility account, including payment of the credited amount,” the report reads. “Since the City employee’s abuse was not detected, the Utility Department risked other employees becoming aware and also abusing their positions for financial gain. In addition, financial gain resulting from City employees abusing their positions would risk eroding the public trust by demonstrating a lack of commitment to ethical and equitable public services.”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Dec. 14, 2025

Belting it out

Legendary

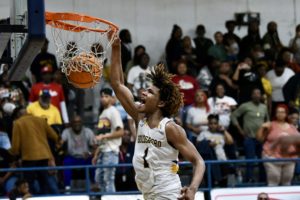

Final Four!