His eyes on the prize

It’s six o’clock in the morning and the sky is starting to brighten, but the streets that separate the apartment buildings tucked inside the West Haven housing projects remain dark.

The groups of young men who were running the block a few hours earlier have dissipated.

For a few moments, it’s almost peaceful in the environment that has seen so much tragedy over the years — teenagers gunned down before their prime, addiction, poverty.

And it will be quiet for a while longer, calm before morning commutes, the rumbling of school buses, and the crack of garbage being compacted by city sanitation crews.

Right now, the only sound, save for a dog’s bark or the chirping of birds, is a teenager’s sneakers hitting the pavement.

Shy Ashford prefers it that way.

Being alone — or, at least, separated from the tough environment he has lived in all his life — has been a saving grace.

It might have even kept him alive.

The high school senior could have fallen into the “street life” that has claimed too many of his peers to count.

He could have lived up to the low expectations certain Wayne County residents have for those raised in the projects.

But thanks to the love of his father and grandfather — and countless lessons learned since he was old enough to really absorb them — he found his home inside a boxing ring.

And every time he climbs through the ropes, he finds peace.

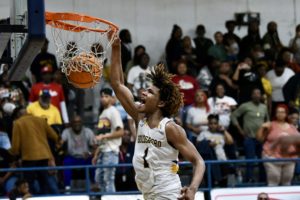

“You make choices. I didn’t have to do this. I didn’t have to box,” Shy said. “I could be out there doing all that, but everybody’s got their own mind and my mind tells me this is where I have to be. I knew that boxing was the best place for me. It was a place I could let all my stress and my anger out. I would hit that bag and just let it all out there.”

Let it all — from typical teenage angst to everything that comes with being a product of West Haven — out.

“It was the area. It was all that — getting caught up in the mix,” Shy said. “When I’m in that ring, it’s gone. When I realized that, I knew I was doing the right thing wanting to take a different route because I’m different. I’m built different and that’s one of the things I love about being me.”

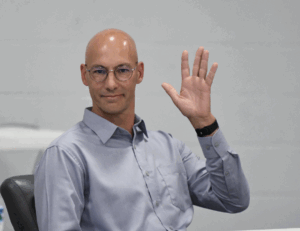

His father, Steve, smiles.

“We couldn’t get nowhere that other way. We weren’t going to reach our goals living that street life. The whole goal was to be successful and then reach back,” Steve said. “We had to start from the bottom, but for me, that’s part of the story. Yeah, Shy is from the projects. He’s lived in the projects all his life. But we want to give back and for me, giving back to this community, sometimes, is just letting them watch him and where he’s going.”

And next month, thanks to his meteoric rise through USA Boxing’s amateur ranks, he’ll be going to the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs to continue to hone his craft and showcase all he has learned since the day, at 4 years old, he first pulled on a pair of gloves.

“I’m excited. It’s that work — mentally and physically — it just makes me happy. It’s just something I need,” Shy said. “I don’t know how I would be without it. I’d be lost without it. It’s like home.”

•

Growing up in the inner-city — and slipping, briefly, down the wrong path — gave Steve a perspective he says enabled him to raise his son the right way.

When Shy was a little boy, looking back and taking the time to truly understand both why he had successes and what led to his failures during his own childhood set the tone for the kind of father he strived to be.

His own dad, the late Steve Ashford Sr., loved him unconditionally.

“My dad knew how to discipline you. He could pull you in and pull you out without being too hard. He just believed in us,” Steve said. “And I didn’t understand the sacrifices he put in, but it takes somebody to believe in you.”

And when he played football at Goldsboro High School, he found, in legendary coach Elvin James, a role model who held him accountable for his actions both on and off the field.

“A lot of us got help from football,” Steve said.

So, it seemed clear that a positive male role model combined with dedication to an extracurricular activity was a formula for success.

But seasonal sports — and long gaps in between mentorship at GHS — allowed bad habits to creep in outside of his home.

“So, I got in the streets,” Steve said. “Football, basketball, they are seasonal. So, a coach can only get his hands on you a little bit. But if you have a boxing coach, he’s almost like your father.”

The owner of Ashford’s Boxing Club — which, in the middle of a December afternoon was packed with students of all ages — looked over at one of them.

“I had you since you were hold old?” Steve said.

“I don’t know,” the young man replied. “Maybe 13.”

“And how old are you now?” his coach asked.

“Twenty-four,” he said.

“He’s been coming here five days a week. That’s what I’m talking about. It’s non-stop. That’s the difference. The ones who end up in that life, they don’t have this,” Steve said. “It’s always the lack of the fathers or the lack of that masculinity in their lives. They don’t have that around and they need that. Half of the kids that are at Goldsboro (High) had the same opportunity, but they won’t even show up. I don’t know what it is about that world. I guess somebody has got to do it first and the rest will follow.”

And now that Shy has more championship belts and medals than he knows what to do with, his father believes he is that “first” who has the ability to change the face of the inner-city that raised him.

“I feel like kids, the really young ones, they look up to me,” Shy said. “That’s what makes me happy. So, the next step is to get better — to keep going. I want the kids to look up to me.”

•

It was just after noon and Shy was in class when a group of teenage boys came looking for him.

A fight would ultimately ensue.

Shy only transferred to his father’s alma mater from Wayne Preparatory Academy because his grandfather wanted him to “get a taste of his own people,” Steve said.

“It is what it is. When he got over there, there were problems,” he said. “At Wayne Prep, it was totally different. He got all As and Bs. But when I sent him over to Goldsboro, everything changed.”

But despite the fact that his public high school experience was short-lived — that he is finishing up his senior year at Wayne Community College — both the father and son consider his GHS experience a blessing.

“It was partially my fault because I told him when he was little, ‘Don’t back down. Because if somebody slaps you today, what are they gonna do tomorrow?’” Steve said. “But he learned something so valuable. You can’t get him to fight right now outside of the ring. Tell him why, Shy.”

“I hurt my hand,” Shy replied, adding it took six months to fully heal. “I missed so many fights and so many opportunities.”

But that wasn’t the only lesson he gleaned from the incident.

“It helped him to learn that, if we get into a street fight right now, what are you gonna do, Shy?” Steve said.

“Back up,” his son replied.

“Why?” Steve fired back.

“Because I fight,” Shy said. “This is what I do for a living.”

Steve smiled.

“And you the what?” he said. “I said, you the what?”

Shy straightened his back and looked his father in the eye.

“I’m the ticket,” he said.

Steve rises from the bleachers and points at his son’s chest.

“That’s right, son. You’re the ticket,” he said. “And the ticket can’t get caught up in the mix.”

•

Success and failures — both inside the ring and outside the ropes.

Like his father, Shy learns from his victories and his shortcomings.

And it is that attention to discipline —a result, Steve said, of his son’s commitment to his health and education — that sets him apart, from the streets of West Haven to the venues across the nation he has walked out of with championship belts secured to his waist and medals hanging around his neck.

“If you get out of school every day and all these other kids are smoking weed and drinking and chasing girls and you go home every day, that says something,” Steve said. “My dad told me, Shy used to get out of high school every day, and my dad helped raise other kids, but he told me Shy is the first kid he had ever seen who got out of school and came straight home. He said, ‘He’s different.’”

So when, the roughly a dozen times out of some 75 fights Shy has competed in that he ended up on the wrong side of the judge’s decision, he didn’t hang his head.

“Tomorrow is another day. It’s gonna get better,” Shy said. “Just keep pushing. Because two years ago, I wasn’t this good. But I kept going. I kept pushing. Look at me now.”

And when he studies boxers’ film to sharpen his skills, he doesn’t simply focus on the household names and champions.

“If you want to learn more, you got to do what?” Steve says.

“Study,” Shy replies.

“That’s right,” his father barks back. “And the more you learn, the more you’re going to be confident in what you do.”

Shy nods his head in agreement.

“I watch all of them,” he said. “I learn something from everybody and put it in my mind.”

But what sets this particular fighter — and his father/coach apart — is that they don’t limit themselves to studying a boxer’s craft.

“We watch their lifestyle, too,” Steve said. “If they have a bad lifestyle, if they party, I show him them, too. I show him their failures — like drinking and smoking. He needs to know that his body is his weapon, and he can’t do that stuff.”

•

He might not be No. 1 in his 119-pound weight class just yet, but Shy currently sits at No. 2 in the nation — having narrowly lost a judge’s decision last weekend in the finals of the USA Boxing National Championship held in Lafayette, Louisiana.

But deep down, both he and his father realize that in many respects, he has already won.

In May, he will receive his high school diploma — a milestone they know not every teenage boy raised in the West Haven housing projects reaches.

He has, since he was old enough to compete, kept himself in the minds of those who, one day, will give him a shot at “the bigtime.”

“He’s putting North Carolina on the map right now. He’s off to the races with the big dogs. He has put in the work, and I have always tried to keep him in a circle with the best. It’s paying off,” Steve said. “It took every penny I had. I took him to Nationals every year and all that — and we’d be sleeping in the car — just so they would see our face. And when we went to Nationals this year, everybody knew him. He’s still in that circle. He’s still relevant. That’s what I wanted.”

He has never backed down from an opponent — facing “the best” time and time again with a swagger and confidence many in the boxing world don’t expect from a kid from North Carolina.

“He can be one of the best because nobody has ever beat him up,” Steve said. “To be able to compete with the best and they can’t hurt you, that tells you that you can be the best.”

And, perhaps most importantly, he has formed a bond with his father that transcends what most would expect from a teenage boy from the environment he has been surrounded by all his life.

“It’s a blessing. It’s a blessing that me and him have the bond we have and that we get through together,” Shy said. “We have that bond, and where I’m from, I don’t see bonds.”

So, when — and both the father and son will tell you it’s just a matter of time — the younger Ashford “turns pro,” it will mark the culmination of a journey that began when Steve’s late father passed the parenthood torch to his namesake.

“This is just special. That’s all I can really say. I told Shy, I said, ‘You’re going to be the best boxer North Carolina has ever had.’ Why is that? Because we go after it,” Steve said. “We go get it. So, if you’re looking for us, wherever the best is at, that’s where we’re going to be.”

Because win or lose, Shy won’t be satisfied unless he has those moments of peace when he climbs inside the ropes — and the opportunity to prove that anyone, from anywhere, can overcome adversity when they have someone like his father in their corner.

“I know he’s got me, and I feel like everybody’s got someone,” Shy said. “But it’s up to you to make the choice to let them be there for you. It’s up to you to take what they teach you and turn it into something.”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Feb. 22, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!