A home invaded. A life interrupted.

It’s the middle of the night and Christian Hernandez’s heart is racing.

The 20-year-old had closed his eyes a few hours earlier, but his sleep was abruptly interrupted when he saw his sister in his dreams.

There is a massive gash on her head.

“You could see her whole skull,” Christian said.

There is blood “everywhere.”

Her hands are bound — duct taped behind her back.

In between being repeatedly pistol-whipped and having her head slammed into an active burner on the stove, the 19-year-old is pleading with the three armed men who, for the last 30 minutes, had been “torturing” her and her teenage brother.

“Then, they kill her,” he said. “I see my sister getting killed right in front of me.”

It is frightening because it is very close to what really happened one night six years ago — a terrifying combination of what could have been and what was.

Christian can’t turn the nightmares off — or forget what it felt like to be there when three men broke into his family’s home.

And it plays over and over again — each time worse than the last.

“I go back and think about what happened that night and I get emotional. I couldn’t do nothin’,’” Christian said. “I know I was young. I know I was only 14. But I hate how I just sat there and watched my sister get hit like that. She’s bleeding out and I can’t do nothing.”

And ever since he and his sister were left for dead in the trunk of a car parked outside their family home on Peele Road back in June 2017, the nightmares that have haunted Christian during his formative years have only been a part of the young man’s struggles.

No matter how hard he tries to move on from what transpired that day — the therapy, the settling down and starting a family — he can’t seem to shake the feeling that his innocence was stolen from him, that his life might have followed a different trajectory had that home invasion never happened.

But at least, he thought, things couldn’t get worse.

Then, a friend sent him a screenshot of a news article that appeared on newoldnorth.com in September.

The story contained shocking allegations delivered by a federal prosecutor in a Raleigh courtroom.

A Wayne County lawman, the government claims, orchestrated the home invasion that nearly cost Christian and his sister their lives.

And it wasn’t just any deputy.

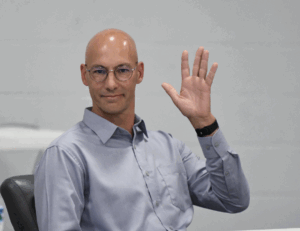

It was, according to prosecutors, former Wayne County Sheriff’s Office Drug Unit chief Mike Cox, the man who led a controversial raid of Christian’s family home in 2011 and arrested his father.

“I wish this would just go away — all this pain — but now, I can’t avoid it, you know? Before, not knowing who did it, in a weird way, it made it easier. Like, maybe it was random or something and they had the wrong house,” he said. “But now, every time I look at (a WCSO deputy), it’s like, ‘One of you did this to me and my family. I was just a little kid. My sister was only 19. How could you do this?’ I feel like I have to look over my shoulder everywhere I go.”

•

It’s the middle of the afternoon and Cox is led into a federal courtroom by a U.S. Marshal.

The 48-year-old was supposed to appear before a judge hours earlier, but his bond hearing was delayed because of a transportation issue.

His hands and feet are bound — shackled with metal chains and cuffs.

In between being repeatedly accused by Assistant U.S. Attorney Dennis Duffy of being a “danger” to his community and having Federal Magistrate Judge James Gates deny his pre-trial release, the former deputy listens as the government reads a series of text messages Duffy said proves several shocking allegations.

“He took his badge and used it as a weapon,” Duffy said. “It staggers the imagination.”

One of the alleged examples of that left Christian stunned.

It was May 18, 2017.

Cox, according to a sprawling indictment handed down by a federal grand jury Aug. 17 and made public by U.S. Attorney Michael Easley Jr. Aug. 30, texted, to a Goldsboro drug trafficker, a photograph of Christian’s father which was obtained from CJ Leads, a secure database for use solely by law enforcement.

Less than a month later, he sent the man another text, the government claimed — a message that included a “pin drop” providing the “exact location” of what Cox allegedly stated was “the man’s house.”

The drug trafficker responded that he was “going to pay em visit,” and, the following day, allegedly texted Cox again to tell him he “went out there n scoped it out.”

Ten days later, Christian was inside that house on Peele Road playing video games in the living room next to the kitchen while his 19-year-old sister cooked.

His father, who was on supervised probation following a six-month prison term and living across town, had not been in the residence since he took an Alford plea for allegedly attempting to traffic cocaine.

“I was playing my game and I had a headset on, but I started feeling, you know how in older houses you can feel the vibrations when people are walking?” Christian said. “Well, it felt like it was more than one person. Then, it felt like somebody was running through the house.”

Worried about his sister, he took off his headphones and jumped out of his chair.

“That’s when I heard my sister screaming,” he said.

Christian started running toward the hallway, but froze when one of the two men who was “on my sister” pointed a gun at his chest.

“He said, ‘Freeze. Don’t move,’” Christian said. “That’s when they took us in the kitchen and duct taped us.”

Their hands now bound behind their backs, the brother and sister were dragged to the living room.

At that point, a third intruder emerged.

“They were screaming, ‘Where’s the money at? Where’s the money at? Where’s the drugs?’” Christian said. “We kept telling them we had no idea what they were talking about.”

But his sister had access to the family’s savings — not even $1,000 — and gave it to the men.

“They got mad,” Christian said. “They said, ‘That ain’t what we’re looking for. Don’t play with us.’”

And then, “boom.”

“They pistol-whipped her,” Christian said. “She’s screaming. She’s bleeding. Boom. They pistol-whipped her again.”

Moments later, they dragged her to the kitchen and slammed her head into an active burner on the stove — leaving a “massive” wound that exposed her skull.

“I thought she was gonna die, but I’m only 14 years old. I’m telling them, ‘We don’t know what’s going on,’” Christian said. “Bam. They pistol-whipped me.”

The violence would continue for nearly a half-hour.

“They kept hitting me with the gun and at one point, they hit me in the face and I had blood spraying out of my nose,” Christian said. “I was on my knees and when they hit me that last time, I fell. I tried to open my eyes, but I was real dizzy.”

That’s when the teenage boy blacked out — regaining consciousness only as two of the men dragged him outside and threw him into the trunk of a car before, not even a minute later, “stuffing” his sister next to him.

“They shut us in there, but I could hear them talking. One of the guys got mad because they didn’t find nothin’ and said, ‘(Expletive) this. They got to die,’” Christian said. “They were about to come kill me and my sister.”

Luckily, another of the three talked him out of it, saying, ‘Don’t make it worse. Let’s go. Let’s just go.’”

And when they finally left, Christian pulled the emergency latch inside the trunk and he and his sister drove to their aunt’s house.

911 was called, but as they waited for first responders, the brother feared his sister would die before help arrived.

“There was blood everywhere. My sister, I think she was getting ready to bleed out. Her whole head, it was just covered in blood,” Christian said. “And I was drenched in blood. The police, they kept asking us, ‘Did somebody die? Did somebody die?’ They found so much blood.”

But despite the recurring nightmare the young man says has played out nearly every night since, neither was killed.

Christian had a severe concussion and a fractured jaw.

His sister, who was in much worse shape, was treated and, like her brother, ultimately recovered physically.

But neither, Christian said, has been “OK” since that home invasion.

And while his sister does her best to live a “normal” life, her brother says he spiraled shortly after the experience.

“My head was (expletive deleted) up, so I basically dropped out of school right after it happened,” Christian said. “It was so hard for me to pay attention. I would look at the board and the teacher is teaching and I am just zoning off thinking about that other stuff.”

On top of that, he felt like he “couldn’t be home,” so he “started roaming the streets.”

“In my mind, I didn’t have a choice,” he said. “I started staying with friends.”

When he tried to sleep, the smallest break in the silence would set him off.

“I would hear noises outside and … run to the window to make sure nobody was breaking in,” Christian said. “So, I didn’t sleep. I couldn’t sleep. I would stay up all night until the sun came up. It’s still like that.”

And when his body finally shuts down — when he is forced to close his eyes — he relives the events that unfolded six years ago, but with a more jarring ending in which his sister is gunned down.

“It’s like I can’t forgive myself. I couldn’t protect her,” Christian said. “I would rather they would’ve killed me than beat on my sister like that.”

The allegations made by Duffy on behalf of the federal government during that September bond hearing were not the first claims made by an attorney about Cox and his alleged involvement in “unlawful” incidents at the Peele Road house where Christian and his sister were “tortured” in 2017.

Back in 2011, the former deputy arrested the siblings’ father, Abel — charging him with trafficking cocaine.

But defense attorney Charles Gurley, according to a “Motion to Suppress” obtained by New Old Northvia a records request, argued that much of the evidence should have been invalidated.

His reasoning included:

• The Wayne County Sheriff’s Office executed a “knock and talk” with “no probable cause” and “without a search warrant.”

• No search warrant “was ever obtained in this matter” and “there was no reliable information used to attempt to obtain a search warrant.”

• The “knock and talk tactic” was used “in order to avoid having to obtain a search warrant” because there was “no probable cause to obtain one in the first place.”

• Nobody at the residence, according to sworn affidavits attached to the motion, granted the deputies consent to enter the home.

• Abel “does not speak English” and “never gave anyone consent” to search or enter the residence.

• The officers “could not have entered the residence since they had no search warrant or arrest warrant if denial was made by any of the occupants.”

Several years after his arrest, Abel accepted an Alford plea — conceding that there was enough evidence to convict him while maintaining his innocence — on one of the felony charges he was facing.

The terms of the deal landed him in prison for six months and required him to wear an ankle monitor upon his release.

Christian said Abel never returned to the family’s Peele Road residence after his release and that given the fact that his father was on a 24/7 monitoring program — and confined to the house he was living in across town — he doesn’t understand why anyone would have suspected there were drugs and money in the home when the three men broke in that night in 2017.

And Abel was never convicted of the trafficking charge, as he was deported to Mexico in 2018 before the legal process played out.

•

It’s late in the afternoon and Christian sips a coffee inside Café Le Doux.

He chooses a seat facing the front door and looks up every time someone enters the shop.

He bemoans the fact that he dropped out of school and has “lost” so many years — that he has worked a number of jobs, from Case Farms to Georgia Pacific, but can’t hold one for long because of “memory issues” and debilitating pain he says he has suffered from since the 2017 attack.

He admits he is paranoid that he is being targeted now that his attorney has notified WCSO officials that he will be filing a grievance against the office for Cox’s alleged involvement in the home invasion.

“I hate the fact that I have to look over my shoulder everywhere I go,” he said.

And he tries to reconcile the fact that he, somehow, paid for the crimes of his father at just 14 years old and in the time since — crimes he said Abel hid from his family until the night in 2011 when Cox and other deputies searched his home.

“My dad was very secretive. I never knew he was into anything (illegal) until they raided the house. We grew up in a loving environment,” Christian said. “Until they raided the house when I was 10 years old, I was innocent. I never knew about drugs. I didn’t know about guns. Nothing like that.”

Even harder is the internal battle — the part of him that, while he understands that what his father did was wrong, still loves the man he knew before his arrest and wants to believe he had no choice but to do whatever it took to ensure his family survived.

“I still love him. He said he did it for us,” he said. “And I’m not gonna lie. Back then, we were in a state where we didn’t know what we were gonna eat that day.”

•

After more than an hour, Christian manages a smile when he talks about the woman he loves and the baby boy the couple is expecting in a few months.

But when he is asked about what his dreams are for his family, he, without realizing it, goes back to that night in 2017.

He doesn’t talk about where they might live or what his son might grow up to be.

“I want to be able to show my family how to protect themselves,” he says.

And when he talks about what he plans on doing until his dream of owning his own business comes to reality, he does it again.

“I was thinking maybe I could be an armed security guard,” Christian said.

The truth is, through therapy, he hopes his mental health will continue to improve — that he can “live a normal life, a happy life, without having to worry about watching over my shoulder.”

But his mind is fixated on “safety,” and “protection.”

And Christian has accepted the fact that he might never fully recover from the trauma he suffered those many years ago.

The truth is, he will never feel complete until justice finds the people responsible for the “hell” he lived and the “constant nightmares” he endures.

“I’ll be honest with you. I used to ride around Goldsboro hoping I would run into the people that did this to me — to my family,” Christian said. “But I’ve decided to go at this another way. I’m not going to put justice in my own hands. I’m gonna have faith that the law will work all this out.”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Jan. 18. 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!