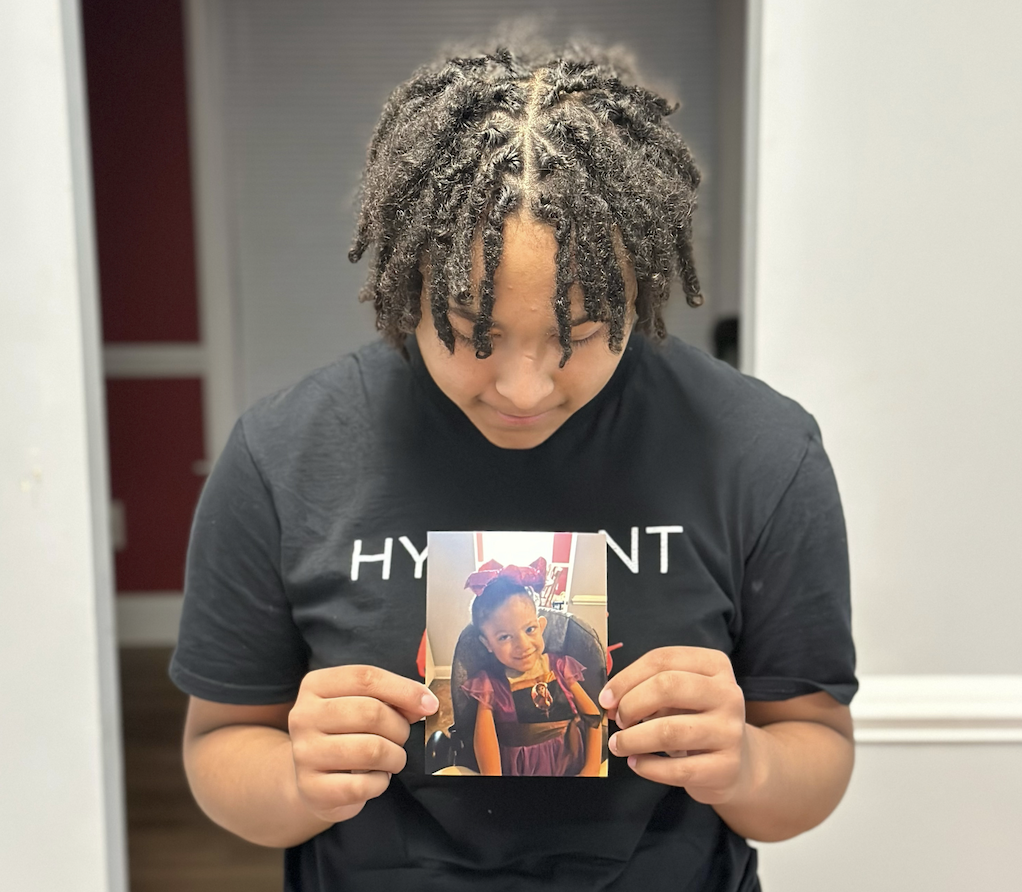

Jayda’s gift

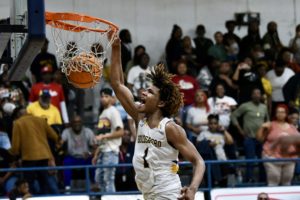

Aleah Hill drives toward the basket and pushes off with her right leg — elevating before softly lifting the ball through the net.

The crowd goes wild, but the 14-year-old is focused on a single chant coming from the bleachers.

“I can hear her in the stands. ‘Go Leah. Go Leah,’ That’s all I hear,” she says. “Even when I’m at practice and I just don’t feel like doing it, all I see is her telling me, ‘Don’t give up. Keep pushing.’”

The basketball court isn’t the only place Aleah sees her 4-year-old sister, Jayda.

She’s everywhere — smiling through the pain she has felt since birth; laughing through the bi-weekly surgeries and casting that helps her manage her affliction, a rare form of arthrogryposis multiplex congenita; squealing with joy as she rolls around the living room floor with her toys.

“She always had a smile on her face. You would never see her down,” Aleah said. “No matter how much she was hurting, she would always bring joy and happiness.”

Had.

Would.

Even now, more than two years after Jayda’s death, her big sister finds it difficult to reconcile that when she speaks about the little girl who is, now, her “angel,” it’s in the past tense.

The truth is, in Aleah’s mind, most of the time, it feels as though she never left.

•

Eddie Abrams pulls out his phone and scrolls through a digital photo album.

He pauses when he gets to the video he was looking for and then hits play.

Jayda’s high-pitched squeal is followed by uncontrollable laughter as she rolls around on the carpet.

She never met her goal of walking, but her grandfather would tell you she was fiercely independent.

“She would roll anywhere on that floor because she couldn’t get up and walk. And she was the sweetest girl, but if you tried to help her, she would tell you, ‘I can do it. I got it,’” Eddie says, smiling as the video runs it course.

His wife, Judy, jumps in.

“She would use her feet, her nose, whatever she could,” she says. “It was something to see. She never quit.”

And even know, looking back on all Jayda was up against from the moment she was born, it is still hard for her family members to explain.

Where did that fighting spirit come from?

How could a 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-year-old be so determined?

“She was born with her feet up by her ears,” Judy said.

“Her right leg was up her side and her left leg was overtop of her right leg and up her side,” Eddie added. “She was kind of doubled in half.”

And that meant seemingly constant trips to Shriner’s Children’s Greenville — for surgeries to fix her “cupping” feet; so doctors could cast her arms and legs in hopes of straightening her spine.

Aleah, if she could help it, never missed a trip to South Carolina.

She wanted to be there to watch movies with Jayda in the back seat — to lift her spirits and tell her everything would be OK.

She wanted to be her protector — to lie in her bed so she wouldn’t be afraid.

But she had no idea that walking the halls of that hospital would change her outlook on life.

“My eyes were already open (because of Jayda), but seeing (other children) opened them even more. I saw all the things I could do, because seeing them, now I knew what they couldn’t do,” Aleah said. “It strives me to push more and really focus on my dreams and give it all I’ve got. There are so many people who wish they had what I’ve got, but they don’t.”

•

It’s a Tuesday evening in mid-November and the sun has gone down — adding a bite to the chilly wind already being felt by those who have shown up across the street from Goldsboro’s Tent City to serve a meal to the homeless population that resides beyond the tree line guarding their encampment from the railroad tracks.

Aleah is one of a half-dozen in the assembly line packing boxes and filling plastic bags with candy bars, fruit and bottles of water.

Behind her, a group of young children run and play.

Their voices — their laughter — are another reminder of Jayda.

She is the reason Aleah joined Tommy’s Foundation’s effort of feeding the homeless on Tuesday nights in the first place.

Giving back became a way, after her sister’s death, of filling the hole the loss left inside her.

And it was an opportunity to right a wrong — just like those doctors, nurses, neighbors, and teammates who made her sister’s four years as comfortable for her as possible tried to do for her.

“I always wanted to give back to the community, but (Jayda’s death) had a lot to do with it,” Aleah said. “Seeing them coming in and out of the woods, it’s just like, it didn’t seem right. When something’s not right, somebody has to step in and do all they can to make a change. Seeing Jayda go through all that at a young age, it was hard, but it made me realize that if she can do it, I can to. So can you. If she can push through this, I can push through anything. Anyone can push through anything.”

•

Since Jayda’s death in August 2021, Aleah has kept herself as busy as possible.

She takes school seriously.

She plays travel basketball and, at only 14, will see plenty of court time for the Eastern Wayne High School varsity girls’ team this season.

But in her downtime — in those solitary moments — Jayda comes back to her.

So, too, does the grief of losing the little girl who always made her smile.

“I don’t like talking to people, so I have to find ways — in my way — to get stuff off my mind and to make sure I can still be happy for my family,” Aleah said. “I write about it sometimes. I pray. I play my games. I listen to music. And some nights, I just sit there and cry.”

But then, she’ll roll over and see Jayda lying in the bed next to her.

“She used to sleep with me,” Aleah said. “So sometimes, it’s like I see her.”

Or maybe, the flicker of a Christmas light will remind her of the joy the colors brought to her sister.

“We didn’t even, I don’t think we even put a Christmas tree up that first year after she passed,” Eddie said. “Jayda loved Christmas so much.”

So, the family — led by a 14-year-old who has far more perspective and wisdom than they could imagine a teenager could possess — has tried to make sense of their sadness by providing hope for those around them.

On Thanksgiving, they will be serving meals to the city’s homeless population.

And as for Christmas? Aleah will continue a tradition she started a few months after she lost Jayda.

“She came to us at Christmas. Jayda passed in August … and that Christmas, she came to us and told us, ‘Instead of buying me gifts or giving me money, I want to take the money y’all would have spent (on me) and I want to buy gifts to donate to Shriner’s,” Eddie said. “We were kind of blown away.”

But to their granddaughter, it makes perfect sense.

“Knowing everything that they did for Jayda and knowing how much they helped her, it meant everything to me to give back to them,” Aleah said. “It was my way to show them that me and my family appreciate all they did to help my sister.”

•

Aleah drives toward the basket and stops on a dime — pulling up for a mid-range jump shot.

The crowd goes wild, but the 14-year-old is, if only for the duration of the game, in her own world.

“When I’m on the court, everything goes away. Nothing is on my mind,” she says. “It’s all joy and happiness.”

She can forget about how it felt in the days after Jayda succumbed to a seizure.

“I just wanted to give up on everything. I didn’t feel like I was ever going to be happy again,” Aleah said. “My other siblings, I still love them the same, but every time I looked at them, it was like, it hurt.”

She can escape the places in her grandparents house that remind her of the good times spent with “Jayda Bug.”

“When I see something that reminds me of her, it hurts,” Aleah says. “Sometimes, I just want to break down.”

And she can hear, if only for a moment, that little girl’s high-pitched voiced cheering her on from the bleachers.

“She was my biggest fan,” Aleah said. “Just like I was hers.”

So even though the holidays are harder now that she’s gone, the little things Jayda left behind will push her sister — and her grandparents — to meet the season with hope.

Like her love of flickering lights.

“We’ll have a Christmas tree out here, but Aleah wants one in her room this year, too,” Judy said. “All the lights will remind her that Jayda’s still with her.”

Like the way the little girl seemingly always looked skyward — as if she could “see something we couldn’t” that was telling her to keep that smile on her face because everything would be OK, Eddie said.

Or, like the day she told her “Papa” that there was a higher power wrapping her with love.

“Out of the blue, she says, ‘You know, Papa, Jesus loves me,’” Eddie said. “For somebody that age to say something like that, it’s like, ‘Where did that come from? She’s only 4. How did she even understand the concept of Jesus’ love?’”

Aleah understands.

Unconditional love, for this particular 14-year-old, is something that finds a way to reveal itself.

And she knows it thanks to her angel.

“It will never go away. My love for Jayda, it will stay with me,” Aleah said. “I am going to forever miss her. And I’m going to forever honor her. I won’t give up. I won’t quit. Because if she knew I was even thinking about giving up, she would cry. All this, it’s for her. I want to be the best person I can be at all times for her.”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Jan. 18. 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!