A link to the past

She only glances down at them for a moment — the used white syringes scattered outside the front of a Goldsboro landmark that has been standing for more than 100 years.

But when Julie Metz approaches a sinkhole in between the back of historic Union Station and a once-bustling platform, she pauses.

“It’s pretty clear that there have been squatters down here,” she says, pointing out the stack of empty beer cans filling the hole. “That’s pretty concerning. It wouldn’t take much to accidentally torch this place.”

It isn’t the first time Metz has had to navigate a piece of the city’s history that has been neglected to a point where it’s on the brink of collapse.

But moments later, standing on the platform where “children used to run around” and families once “shared hugs” and “shed tears,” she regains her focus.

“It’s one of my, I don’t know, one of my God-given talents — to be able to see what isn’t right there in front of me,” she says. “I don’t know. I don’t know how to explain it. But I can see it. I can feel it.”

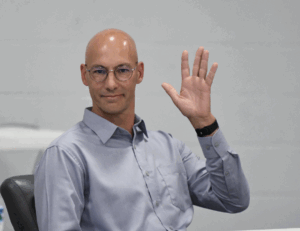

To Metz, who led the city’s Downtown Goldsboro Development Corp. during the rebirth of the city’s core, Union Station represents a swan song of sorts.

After leaving the DGDC, she went to work for the state, and in a few weeks, she will officially retire to a family farm in Pennsylvania.

But then, she got wind of an appraisal report from Birch-Ogburn & Co. — a document that valued Union Station at negative $791,100 and outlined “detrimental conditions found within the property.”

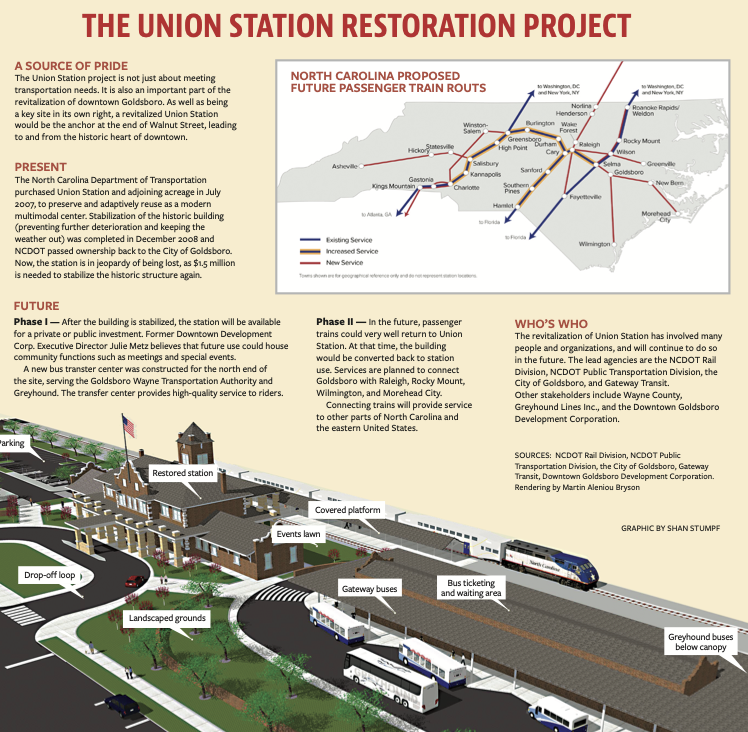

And she learned that without a stabilization effort, one that would cost nearly $1.5 million, the station could quite literally crumble to the ground, and along with it, any chance of future passenger rail service through Goldsboro.

“If Goldsboro loses Union Station, I can’t even tell you how devastating that would be for this community. So, there is no way we can let that happen,” Metz said. “We’re going to save it. That’s the mindset. There’s no way we’re not going to save that train station.”

•

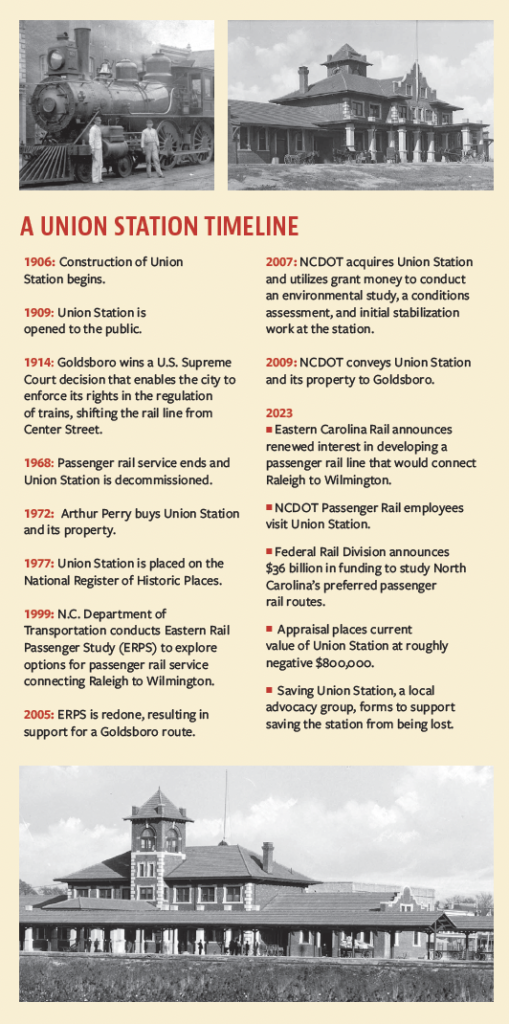

It started in 1906 with $72,024.

“It sounds ridiculous now because it only cost $72,0244 to construct … but that was a lot of money at the time and the whole town shut down the day it was opened to the public to celebrate its potential impact,” Metz said. “Goldsboro was built on this station and the intersection of the three major railways that traversed through here — one of them being the longest rail corridor in the United States at the time at 161 miles. So, we were built because of this building and our forefathers had great ambitions for the citizens of Goldsboro and our community.”

And for more than six decades, until it was decommissioned in 1968, Union Station served its community well — providing, among other things, opportunities for those who simply could not afford more expensive means of transportation, she added.

“Children, they used to run out here. Up and down. Laughing and playing,” Metz said, staring down what used to be an active platform. “They or their parents traversed through this station to get to opportunities — whatever they might have been — to go see other sights, to go to jobs, to get access to services and goods.”

So when, back in 2009, the city held an event at Union Station to celebrate the landmark’s 100th birthday, it came as no surprise to her that local residents packed the grounds.

“At the time, it was probably the most diverse crowd that had ever attended a downtown event,” Metz said. “And if you look at the pictures from that day, you’ll see quite a few people who came in wheelchairs. That says a lot. What that tells me is that it took them a little extra effort to experience that day, but they wanted to ensure they didn’t miss it. And when we talked to them, we found that they were kids at the time (when the station was active). Some of them used to just come down here to play.”

It was more than just a place to board a train.

It was a source of pride for its neighborhood.

And it was a place where everyone — no matter their background — could come together.

Standing outside what used to be the station’s main entrance, Metz looks up the hill toward a downtown she helped revitalize.

She can see the streetscape and light poles installed as part of a TIGER grant she helped the city secure.

She can see, in the distance, the building that now houses the Arts Council of Wayne County.

And she admits it is serendipitous that when the downtown Goldsboro’s revitalization really took off a decade ago, the Arts Council and another “anchor tenant” — the Paramount Theatre, another historic landmark that once needed saving — were drivers of that movement.

“When the Arts Council came downtown — and the reason we got a grant and provided them $200,000 to relocate to downtown and help them manage the construction of upfitting the building they moved into on John and Walnut Street, is because we understood and appreciated the synergy that they would bring — I mean, just the energy and diversity of people it would add to the downtown mix was going to be huge,” Metz said. “And so, it’s an anchor tenant. So, even the synergy between (Union Station) and (the new Arts Council location), it’s palatable. What that energy did for the John Street and Walnut Street intersection, it can now do for the Walnut and George Street area.”

The concept, she said, is not pie-in-the-sky optimism either. The city and its residents have seen, with their own eyes, how restaurants and boutiques started popping up shortly after the Paramount reopened a few blocks away from the Arts Council’s former headquarters.

So, why not assume the same thing would happen on the other side of downtown thanks to a revitalized Union Station?

“You need anchor tenants. You know, malls were built on anchor tenants. You can’t just have one. You have to have multiple to create the synergy and to spur private investment for the holes in between each anchor,” Metz said. “We already have Arts Council right up there. So, that’s what this building would serve, regardless of its use. Union Station would be the second anchor. It’s going to be a game-changer for this neighborhood.”

She took that same pitch — that same argument — to the City Council’s Nov. 6 meeting.

She talked about the appraisal and the cost of “doing nothing” — how demolishing the building and cleaning the site would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and require ongoing landscaping and site maintenance costs.

She unwrapped the millions of dollars spent by the city, state, and federal government that had already gone into the station to date — from TIGER grants and matches to construction of the Goldsboro Wayne Transportation Authority hub that was built next door to the landmark “to honor Union Station.”

She told the council that a group of citizens had come together to form the “Save Union Station” organization, advocates who agreed to raised $750,000 of the $1.5 million needed to stabilize the building for future use.

She noted that when the North Carolina Department of Transportation conveyed the train station and its property back to Goldsboro in 2009, the city agreed, in writing, to keep the building viable for potential future rail use — and that the city was on the verge, after years of neglect, of breaching that contract.

“You tell a story. You show a story. And showing this right now, and the fact that the city took on the responsibility to maintain it — to protect its future use for passenger rail and transit — would be embarrassing,” Metz said. “I would think that the city should be embarrassed. They have clearly forgotten about (Union Station’s) existence over the last four years. Nothing has been done to it. Even the vegetation hasn’t been dealt with. Now, it’s just sitting here neglected and forgotten. It’s just so darned sad.”

She reminded them that the landmark is on the National Register of Historic Places.

“So, there will be protective covenants on it … to make sure that’s it’s available to the public to make sure they are able to visit and experience it,” Metz said. “That protection of public involvement and connection will always be maintained. I think that’s super important.”

She informed them that earlier this year, Eastern North Carolina Rail announced it had renewed its interest in developing a passenger rail line that would connect Raleigh and Wilmington — that in the same timeframe, the Federal Rail Division announced $36 billion in funding to study the state’s “preferred” passenger rail routes.

“They are serious, so we need to be ready,” Metz said. “We can’t afford to let this opportunity pass us by.”

And she compelled the board to act, to pledge $375,000 of the remaining $750,000 so the SUS group could ask the county commissioners to fund the difference.

But where would the money come from?

A fraction of the $2 million awarded to Goldsboro in the recently passed state budget thanks to House Majority Leader John Bell — money that could not, for example, be used to increase first responder pay or other needs — would cover it, Metz said.

Several councilmembers were moved by her presentation — perhaps, the most passionate among them, mayoral candidate Charles Gaylor, who, by the end of the week, could very well be the city’s mayor-elect, as he currently holds a 9-vote lead ahead of the county canvass.

He said allocating $375,000 for the stabilization of the station was the fiscally responsible thing to do, given the fact that private citizens were offering to match funds.

“If someone else says they’re going to match it dollar for dollar, that’s a pretty compelling position to be in,” he said. “I don’t like to pass up the opportunity to leverage funds.”

And he also acknowledged that he and his family have been “very involved in the efforts to save Union Station” for a long time — telling the board “I’m fully in support, and if a motion is made and seconded, I will be voting in favor of allocating the funds.”

It took less than a minute for his fellow councilmembers to follow his lead.

And thanks to a unanimous vote that, arguably, happened because Gaylor was able to focus the board when it seemed they might simply vote to “support” the project without an immediate financial commitment, Metz is now one vote away — one she hopes the Wayne County Board of Commissioners will make at their next meeting — from saving the landmark for its next act, whatever that might be.

•

Metz would tell you that from Salisbury and Rocky Mount to Hamlet, revitalized train stations have become “sources of pride” in communities across North Carolina.

They are tourism magnets and host everything from galas and conferences to family reunions.

“They are utilized in all different kinds of ways,” Metz said. “They attract people from all across the state and beyond.”

So, when, back on that platform, she closes her eyes and envisions what she believes, a few years from now, will be the reality at a station that is currently “salvageable” as long as the county commissioners allocate the final $375,000 needed to stabilize it soon, she smiles.

She had the same feeling back in 2009 when NCDOT gave Union Station and its property back to Goldsboro.

“I was already looking for dresses to celebrate its grand reopening,” she said, adding that the party, a Roaring Twenties-themed event, was already being planned.

And as the once-grand landmark returns to the forefront of minds across the city, the hope she had all those years ago — a hope akin to the one that drove her during the revitalization of other parts of downtown that have since been realized — is burning inside of her again.

“I can see it right now for sure. I can see having annual dinners and parties and weddings out here. I can hear the laughter,” Metz said. “Those things have happened here before. I think we owe it to ourselves to bring that back. This was, I’m not sure I’d go as far as saying it was a sacred spot, but it was a special spot for sure. It’s going to be again. I can just feel it.”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Feb. 8, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!