Behind the badge

RALEIGH — A law enforcement officer watches as, upon his request, a drug trafficker threatens the lawman’s 17-year-old daughter’s boyfriend.

The same officer sells guns he seized from drug raids — firearms he never logged as evidence — on gunbroker.com, a website advertised as “a marketplace of gun enthusiasts.”

He receives illegally obtained painkillers that are dropped, on numerous occasions, in his Walnut Creek mailbox.

He even invites known dealers — one who served time for a murder that was reduced to voluntary manslaughter years earlier — to his home for dinner.

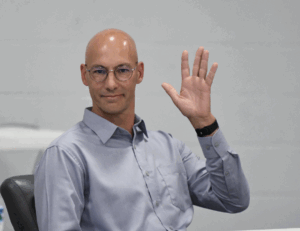

Those allegations combined with other details from an indictment handed down by a federal grand jury Aug. 17 and made public by U.S. Attorney Michael Easley Jr. Aug. 30, were more than enough to convince Federal Magistrate Judge James Gates to deny former Wayne County Sheriff’s Office Drug Unit chief Michael Cox release from custody as he awaits trial.

•

Early Wednesday afternoon, Cox, dressed in a bright orange jumpsuit, shuffles his way into a courtroom on the sixth floor of the Terry Sanford Federal Building — his hands and feet shackled.

Several members of his family are seated in the gallery.

The former deputy has been charged by the government with 12 counts of fraud for his participation in an alleged bid-rigging scheme and making false statements to the FBI.

But the bulk of Wednesday’s marathon hearing focused on his alleged conspiracy with multiple drug traffickers to distribute and possess with the intent to distribute cocaine and oxycodone.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Dennis Duffy outed two men who, before the hearing, were known simply as “Drug Trafficker One” and “Drug Trafficker Two.”

One of them, Rinardo Howell, is a convicted drug dealer who is currently serving two 188-month sentences in federal prison. He, prosecutors told the court, is “Drug Trafficker Two.”

The other, Theodore Lee, stands accused of trafficking methamphetamine, cocaine, crack, fentanyl, oxycodone, heroin, and marijuana, according to a March 21, 2021, indictment obtained by New Old North. He, according to the government, is “Drug Trafficker One.”

So, how did Cox come to know these men?

How, as the government alleges, did he conspire with them?

The following events are detailed in the Aug. 17 indictment and form the basis of the case against Cox, as it relates to “Drug Trafficker Two,” identified by the government as Howell:

• On May 18, 2017, Cox texted (Howell) a photograph of a Peele Road drug dealer, which was obtained from CJ Leads, a secure database for use solely by law enforcement. The text also included a pin indicating the location of the Peele Road residence and stated “(t)hat’s the man’s house.” (Howell) indicated that he would be “paying em visit.” Just 10 days later, there was a violent home invasion at the residence, and according to the indictment, even though Cox had knowledge of Howell’s possible involvement in the home invasion, he said nothing. During Wednesday’s hearing, Duffy characterized the home invasion as including “elements of torture” — describing the pistol-whipping and duct-taping of juveniles and slamming a girl’s face into a stove with the burner on.

• On June 26, 2017, Cox observed (Howell) purchasing two ounces of cocaine from a target whose home was being watched by Cox as part of a DEA operation. Instead of arresting him, “Cox pulled over (Howell) and explained that the drugs would need to be seized because the DEA was targeting (Howell’s) supplier.” (Howell) complained that he would be out the $2,000 used to buy the drugs. In response, Cox “stated that he would use buy money to reimburse (Howell) and make it appear as if the situation had been a controlled purchase, which it was not.” Cox, the indictment alleges, paid (Howell) the $2,000 and a $200 confidential informant fee.

• On Sept. 27, 2018, Goldsboro police and the Sheriff’s Office executed dual search warrants on houses used by (Howell). He was arrested and his cell phone was seized. After (Howell) was released on bond, he called Cox and was instructed to come to his home in Walnut Creek. Cox, at the time, was still a sworn WCSO deputy. He was hosting a cookout with the head of the WCSO Patrol Unit and a defense attorney. Upon arriving at Cox’s house, the indictment alleges that (Howell), the defense attorney, and Cox discussed the search warrants and then Cox arranged for the attorney to handle (Howell’s) case. During the hearing, Duffy identified the attorney as Goldsboro attorney Worth Haithcock.

• Cox later called the GPD drug unit and demanded that investigators turn over (Howell’s) phone to the WCSO. The head of the GPD drug unit refused. During Wednesday’s hearing, an FBI special agent testified that Cox contacted the GPD and “tried to get the phone back” because, as the prosecutor put it, “He knew what was on that phone.”

• Cox’s official retirement date was Oct. 31. On Nov. 5, 2018, Cox and (Howell) texted about which witnesses the defense attorney should call at an upcoming suppression hearing relating to GPD and WCSO’s dual search warrants. Charges against (Howell) were dismissed on Jan. 9, 2019. In the meantime, now that Cox was gone, the WCSO’s new head of the Drug Unit proposed that GPD join WCSO in a drug task force, which was to be housed at a new, shared facility. The indictment alleges that the city had been unwilling to join such an effort in the past because investigators believed Cox was “improperly protecting (Howell).”

• On Feb. 15, 2018, (Howell) texted Cox a photograph of 14 oxycodone pills stamped “K8” and texted “(t)here,” to which Cox responded, “(t)hanks.” (Howell) texted back, “No problem it’s 15,” which the indictment alleges was a reference to a price per pill. Four days later, on Feb. 19, 2019, (Howell) shot a cooperating informant who the joint WCSO-GPD task force “had planned to use to make buys from (Howell).” The wounded informant survived and called 911, telling the operator he had been shot by (Howell). A detective arrived at the hospital that night to check on the victim. According to the report, 90 minutes later, the detective received a call from Cox. According to the detective, Cox stated that he had heard (Howell) was being accused of shooting someone. According to the indictment, Cox said, “(Howell) didn’t shoot nobody he was texting and facetiming me all night during the Carolina Duke basketball game … he wasn’t at Slocumb and Mulberry.” During Wednesday’s hearing, Duffy argued that Cox was “busy creating an alibi” for Howell when, the prosecutor alleged, “he knew it was (Howell) who shot the C.I.”

• On Feb. 21, 2019, Cox texted (Howell) and directed him to “go up to the shop. (a worker) is gonna fix u.” The indictment then alleges that Cox texted the following to (Haithcock) the next morning, “(Howell) has attempted murder warrant. It’s bullshit. … (Howell) has got like 1500 cash if you meet him at the magistrate office just try and get his bond at 200,000. He said he can make bond if it’s 200,000. Let me know if you can help him.” (Haithcock) told Cox to tell (Howell) to “lay low” until he could meet him at his office. Cox indicated that he passed the message along to (Howell).

• On March 1, 2019, (Howell) and Cox exchanged messages. (Howell) texted, “My bruh for life … (expletive deleted) who don’t like it.” On March 3, Cox responded, “I know u do. U know I have your back through anything. There ain’t many people you can trust in life. But ur my bro.”

• On June 27, 2019, according to the indictment, (Howell) texted Cox again, this time to discuss the arrest of another drug trafficker. Cox indicated he did not have any information to share yet, but discussed via text with (Howell) the possibility of getting DT3’s bond reduced to $75,000. Cox allegedly told (Howell) to put money on DT3’s canteen account at the jail and that Cox “would take the amount out of what (Howell) owed Cox.”

• On Dec. 4, 2019, (Howell) was arrested by WCSO in possession of two kilograms of powder cocaine. After the arrest, Drug Unit Subordinate, who was previously mentioned in the indictment in connection with an alleged incident involving Cox, drove (Howell) to be interviewed by investigators. During the drive, Cox called Drug Unit Subordinate One, who did not answer the call. Drug Unit Subordinate One was assigned to make a copy of (Howell’s) cell phone. According to the indictment, upon learning that (Howell’s) cell phone had been dumped, Cox sent a text to Drug Unit Subordinate One, “I know you dumped ((Howell’s) phones and have read all the text messages. Why didn’t you say anything abt when I talked to you earlier. I really don’t give a shit. Cause there ain’t nothing on any of his phones that would get me in trouble. But damn!! Why is everyone so secretive? I hope somebody comes to speak to me. Cause I will blow the roof off that dumb ass office!! Thanks for looking out.” When he did not receive a response from Drug Unit Subordinate One, the indictment alleges that Cox texted the following: “I knew something was up when you said you were going to help me at the shop and you never came or called. You know if it weren’t for me you wouldn’t even be there now. They wanted you gone. And thought you were dirty and I stood up for you. In fact I got fired because of the whole situation I had your back to the end. Investigate all y’all want to. There is nothing I have said or done that is remotely illegal. Lose my number. You don’t ever have to worry abt talking to me again. YOU LIAR.”

The following events are detailed in the Aug. 17 indictment and form the basis of the case against Cox, as it relates to “Drug Trafficker One,” identified by the government as Lee:

• On April 26, 2018, (Lee’s) image was captured on a video entering a drug stash house in Goldsboro “with a handgun in his right hand and then exiting the house minutes later,” the indictment alleges. After (Lee) drove away, another dealer was seen “limping out of the house with a gunshot wound to his leg.” After the incident, (Lee) contacted Cox and asked him to let him know if law enforcement were looking for him. (Lee) was arrested and charged on May 5, 2018, but the charges were dismissed, the indictment alleges, on May 17, 2018, after the victim “signed an affidavit stating that (Lee) had not shot the victim.”

• On Jan. 7, 2020, the indictment alleges that a close relative who lives at Cox’s residence asked him if he could contact (Lee). “You think (Lee) could get me something in the next few days. I have cash.” On Jan. 16, 2020, the close relative — identified in Wednesday’s hearing by Duffy as Cox’s wife, Rebecca — indicated that there was “not one thing in the mailbox not even mail. You’re gonna have to threaten that sorry (racial slur deleted).” Cox responded later that (Lee) “was still looking.” After that exchange, Cox and (Lee) texted at least 30 times during the remainder of Feb. 5, 2020.

• On Jan. 24, 2021, according to the indictment, Cox texted (Lee) about getting some Percocet/oxycodone pills. (Lee) then began communicating with his suppliers to set up a deal with Cox, and calls were made by two pill suppliers. On Jan.25, 2021, (Lee) called and informed Cox of the identities of the two suppliers from whom he could get the pills and explained that the available supply would be limited to “10 pills at $15 per pill.” (Lee) also indicated that Cox would have to split the pills with him. And, according to the indictment, Cox agreed. A text discussion was held three days later negotiating prices for more pills, to which Cox agreed. According to the indictment, (Lee) agreed to deliver the pills to Cox’s home mailbox. “A review of data from a GPS device that had been placed on (Lee’s) car shows (Lee) driving to the Walnut Creek subdivision where Cox resided.” The GPS device was placed by the ATF pursuant to a federal court order.

• On Jan, 29, 2021, (Lee) texted Cox again and asked about delivery for the original 15-pill order. And after a series of texts, they agreed to the same mailbox delivery.

• On Feb. 25, 2021, (Lee) used his original cell phone to alert Cox that a GPS device had been found on his car during an oil change. He reminded Cox that he had made deliveries to his home with that vehicle. (Lee) said he pulled it off the car and told Cox that he had posted a picture of it on Snapchat.

• After receiving the call from (Lee), Cox tried to call the WCSO Drug Unit and Drug Unit Subordinate One, who spoke to him for less than two seconds. Cox also made calls to other Drug Unit members. From those calls, the indictment alleges, Cox “surmised that the GPS device was part of an ATF investigation.” Cox then called (Lee) to warn him about the ATF investigation. (Lee) then called his drug associates to warn them as well.

•

Hart Miles, a partner at Cheshire Parker Schneider, PLLC, who represented Cox Wednesday, compelled the court to grant his client pre-trial release.

He said that despite the absence of official paperwork, Howell and Lee were informants — that just because Cox allegedly bought illegally obtained pain pills doesn’t make him a drug trafficker.

He also noted that his client doesn’t have a U.S. Passport and has known about the pending charges for more than two years but “didn’t try to run and hide.”

Miles characterized the government’s evidence as “very speculative” and questioned whether Howell and Lee were given anything in exchange for their testimony.

But Duffy said Cox was “a dangerous person.”

He reminded the judge of evidence presented that the government says allegedly proves the former WCSO Drug Unit chief befriended and worked alongside known drug traffickers — that he thwarted investigations and prosecutions for them and tipped them off when law enforcement were monitoring their activities.

“He chose to protect these guys. They were his people,” Duffy said. “These are guys who have murdered people.”

And he retold the story of how Cox allegedly prodded Howell to threaten his then-17-year-old daughter’s boyfriend.

“He got a hardened drug dealer that shot a (confidential informant), he has him go and threaten a high school kid,” Duffy said. “That shows you the way he operates.”

He talked about the “damage” Cox has done to Wayne County — and the reputation of its lawmen and women.

And he repeated an anecdote provided by a witness during which Cox allegedly said he would do everything in his power to avoid a prison sentence.

“He said he wouldn’t go to federal prison,” Duffy said. “He wouldn’t be taken alive.”

But most importantly, the government told the court he blurred the lines between the good guys and the bad guys.

“If you’re a drug dealer, this guy is a unicorn. He literally gave a golden ticket to all these drug dealers,” Duffy said. “He took his badge and used it as a weapon. It staggers the imagination.”

•

Just before 6 p.m. Wednesday evening, Gates delivered his decision on whether or not Cox would be released from prison as he awaits his Oct. 24 arraignment before Chief Judge Richard E. Myers II in a Wilmington courtroom.

He talked about the former deputy’s “deep involvement” and “close relationships” with drug traffickers.

He told Cox that the government had presented “clear and convincing evidence” against him that was “enough to convict you.”

“The government has shown it has a strong case against you,” Gates said.

He talked about Cox’s alleged “willingness to put his family in danger” by allegedly inviting drug traffickers to his home for meals and to deliver illegally obtained pain pills.

And he opined that the defendant was a textbook example of a “flight risk” — and someone who he called a “danger to the community.”

Because of those factors, Cox, he ruled, would remain in federal custody until his trial — a decision that left several members of the former deputy’s family in tears.

But as a consolation for the defense, the judge, at Miles’ request, instructed U.S. Marshalls to ensure Cox was placed in the prison’s protective custody unit because he is a former law enforcement officer.

BREAKING PROTOCOL FOR PROFIT?

For purchases between $1,000 and $2,500, he was required to obtain three independent quotes and award contracts to the lowest bidder.

For anything more expensive than $2,500, he was prohibited from hiring anyone to complete the work until a “purchase order” was approved and signed by Wayne County finance officers.

He was supposed to prepare a one-page “Memorandum of Award” that provided the identities of the three vendors and a list of the three quotes.

He was expected to “never discuss one vendor’s pricing and delivery terms with another vendor” to avoid “unfair competition.”

He was supposed to exercise “honesty and integrity.”

But according to an indictment handed down by a federal grand jury Aug. 17, a sprawling 50-page document made public by U.S. Attorney Michael Easley Jr. Aug. 30, Wayne County Sheriff’s Office Maj. Chris Worth stands accused of failing all of the above — and conspiring with Cox to ensure Cox’s business, Eastern Emergency Equipment, received contract after contract from the Sheriff’s Office to upfit vehicles, including Sheriff Larry Pierce’s 2019 Chevrolet Tahoe.

Both Worth and Cox face 12 counts of fraud relating to the alleged bid-rigging scheme outlined in the indictment.

So, what are the details of the alleged bid-rigging scheme?

According to the indictment, Worth was promoted to captain in charge of Support Services in 2016 and “became responsible for coordinating and vetting bids from vendors for various WCSO contracts.”

Worth was required to submit documentation to county finance officers for approval for any new vehicles as well as for the installation of after-market equipment like radios, sirens, lightbars, decals, etc. — also called an “upfit.”

Those installations also included brackets to hold computers as well as partitions, push bumpers, and customized front center consoles/adjustable arm rests.

Although Worth was required to make decisions on contracts with the best interest of the county in mind, the indictment alleges he also had a great deal of latitude when it came to selecting bids for jobs costing less than $1,000. In this case, the invoice was sent to the county Finance Department, which, in turn, sent a check directly to the vendor.

For jobs costing between $1,000 and $2,500, Worth was required to obtain three independent quotes and award the contract to the lowest bidder.

He was not required to submit the quotes to the county, but he was supposed to keep them in a file in case there was a question, investigators said.

For equipment costing $2,500 or more, Worth was not allowed to award a job until a purchase order was approved and signed by county officials.

There were some limited exemptions in the manual for cases in which there was a sole supplier or if there was a public exigency, investigators said, but even then, the paperwork had to be approved.

To start the process, Worth was required to get three quotes on “the same item and specifications” from vendors and to prepare a memorandum of award, listing the three quotes, with the lowest bid listed first. The entire packet was then submitted to the finance office for review, which was not an exhaustive process, according to the indictment.

“Because of the volume of purchasing packages received on a daily basis, County Purchasing did not have the resources to do a detailed review of each package or to call vendors to confirm the validity of the quotes provided,” the indictment reads. “Instead, County Purchasing relied on the honesty and integrity of various departments and offices that submit the documentation, including WCSO.”

And according to the rules outlined in the manual, those who are taking the bids are not allowed to discuss any of them with other participants in the process.

That’s where Cox’s business, Eastern Emergency Equipment, which he had been operating since 2003 — and where Worth had been moonlighting from 2006 to at least 2021 — comes into the picture.

According to the indictment, EEE got the equipment it used to perform upfit installations from West Chatham Warning Devices, based in Savannah, Ga., which operates branches in several cities.

A sales representative was assigned to the EEE account and worked it for more than a decade.

West Chatham provides upfit services and equipment to many regional law enforcement agencies and has completed contracts with large police departments involving hundreds of cars.

In 2016, investigators say Cox moved his business to a storefront on West Grantham Street in Goldsboro and he and his new wife moved to Walnut Creek.

The indictment alleges that while Worth worked at EEE, he supervised the bid process — that because of his position and his relationship with Cox, he and Cox were able to “fraudulently manipulate Wayne County’s bid process to financially benefit Cox and Worth.”

Here’s a timeline of the alleged offenses:

• Feb. 1, 2016: Worth and Cox communicated by text about a $29,055 balance owed for all the camera and radio installs. After Cox, who was head of the WCSO drug unit at the time, inquired about what kind of letter he would need to write “to get drug money moved,” Worth responded that he needed a quote on the radios since he would “have to pay for it through another account.” Worth than asked Cox to backdate the quote.

• Aug. 9, 2016: Worth and Cox texted regarding work that had already been completed by Cox but that had not yet been authorized by a purchase order. Cox said he was sending an invoice for work done on “the 8 Chargers so you can go ahead and get a po.” Worth then said of the purchase order, “hopefully they will do a blanket PO. Does the invoice have to match the quote? Item for item?” Worth then asked if Cox would have to bill the county for one set of work done and deliver another, with Cox responding that “he had already changed it and emailed it. But I can change it back.”

• May 5, 2017: Worth asked Cox to resend a bill for work done on a Tahoe, saying that “each bill needs to be under $2,500.” By splitting the bill, Worth was able to avoid having to obtain three quotes, which he would then have to submit to county finance officers. Later that day, Cox split the $4,613.28 charge for the single Tahoe upfit into two invoices — which the WCSO received on the same day — but backdated the approval dates to match the invoices.

• May 8, 2017: The Sheriff’s Office received split invoices from EEE for the sale of eight TLR-1 gun lights — also a manipulation to circumvent county purchasing rules, according to the indictment.

Although the invoices were stamped “received” on May 8, Support Services backdated the approval dates to match EEE’s backdated invoice dates.

• Sept. 6, 2017: WCSO’s K-9 Team supervisor sent an email to Cox at EEE with copies to Worth and his second in command at Support Services for three Havis Shield K-9 Insert Crates, adding, “I’ll get the other two from the internet somewhere and get them submitted for the PO. As soon as I get everything back, I’ll get you to order them.” It was predetermined, the indictment alleges, that the bids would go to EEE — even though because the amount was over $2,500, three bids were required. “To meet this requirement, the K-9 supervisor used two internet printouts, with fictitious information added for labor and freight costs, as the competing quotes.”

• On Nov. 13, 2017, Worth texted Cox to negotiate pay owed to him for 20 vehicles on which he had done work for EEE. The indictment alleges Worth was not paid on a weekly basis. He and Cox typically negotiated an aggregate payment due after Worth completed work on a number of cars.

• June 7, 2018: Worth texted Cox and ordered a K-9 crate and electronic door popper from Cox without any attempt to comply with the three-quote requirement.

• June 11, 2018: Worth texted Cox about an invoice done for work on a WCOS boat. When Worth realized that County Purchasing had approved $2,200 but Cox planned to invoice only $1,400, the two men discussed how to add additional equipment to pad the quote to get the price closer to the invoiced $2,200, including deciding unilaterally to add “golight spotlights,” with Worth adding that “If they don’t want it we will put it on something else.”

• Sept. 26, 2018: Cox texted Worth and asked him if he needed to keep Bill Travis’ car under a thousand (dollars). Worth responded, “(I)t would be easier on me.”

• January 2019: Cox installed a truck vault on Sheriff Larry Pierce’s 2019 Chevy Tahoe. The total charge was $2,147.92, which according to the rules, required three bids. To avoid triggering the three-bid requirement, Cox split the cost into two $1,073.36 invoices and then applied a 10 percent discount to bring the amount on each invoice to $972.96. To disguise that the invoices were for the same truck, Cox used different invoice numbers and dates, the indictment alleges. Worth approved both invoices and backdated his approvals to match the dates on Cox’s invoices. The payment was sent as part of a larger check written to EEE, which was sent on Jan. 17.

• September 2019: Cox asked the West Chatham sales representative to provide him with a fictitious quote for a Dodge Charger for EEE to use to get WCSO’s upfit contracts. To curry favor with EEE, the sales representative who considered Cox a friend and a valued client, provided the quote. Cox gave the sales rep a copy of EEE’s quote, so she “was able to inflate the fictitious quote to ensure EEE’s quote would win the contract.” Although the quote was addressed to the WCSO, it was sent directly to Cox at EEE on Sept. 16. The third bid used by Worth to justify WCSO’s award of 14 upfit contracts to Cox was taken from Performance Automotive, the car dealership that provided many of its new vehicles. Worth obtained the one-page printout from the website for the upfit of a 2019 Dodge Charger and used it throughout the year, “whether the upfit contract was for a Dodge Charger or not.”

• In 2019, Worth used the West Chatham and Performance Automotive quotes to justify the award of 14 upfit contracts to EEE. “Although the quotes covered parts specific to a Dodge Charger, the awards related to four Dodge trucks and two Chevy Tahoes” for a total of about $61,545.93.

• April 29, 2020: Worth texted Cox and directed him to prepare a false invoice by stating, “(m)e and Brian got a phone holder each. Will you bill as a pair of shoes.”

• June 4, 2020: Worth sent a text asking Cox to backdate an EEE invoice.

• Aug. 31, 2020: Worth shared the sign-in and password to Performance Automotive’s website, which allowed Cox to check to see if his bid was lower than Performance Automotive’s submission. When he found out his bid was higher, he altered EEE’s bid for adjustable flip armrests to 0. This allowed EEE to beat Performance Automotive’s quote by $31.05, according to the indictment. “In order to recoup the cost of the armrests, Cox would later present WCSO with a separate (bill) for nine of the armrests.”

• Sept. 16, 2020: Cox sent the West Chatham sales representative a copy of EEE’s competing bid for the 2020-21 WCSO upfit contracts. The sales rep used this information to make sure that the fictitious West Chatham quote was higher than EEE’s bid. The bid was sent directly to Cox’s email. It was then sent to Worth’s WCSO email account from Cox’s Yahoo account.

• Cox and Worth used the false quotes from Performance Automotive and West Chatham to win bids for 11 upfit contracts in 2020-21. Although the upfit awards were for nine Dodge Durangos and two Chevy Tahoes, the proposals were for a Dodge Charger. In total, EEE received $49,658.43.

• April 26, 2021: To recoup the cost of the armrest installations EEE removed to win the bid, $968.22 (before taxes), Cox billed for payment for labor used to install decals on the nine Dodge Durangos. To avoid documentation requirements, Cox split up the cost of the decal-related expense into two invoices for $900 and $450. The check was mailed on April 30.

• June 28, 2021: Worth and Cox discussed troubles they might have in competing with the Performance Automotive bids. When he learned that Performance Automotive was no longer listing prices on its website, Worth suggested that Cox get the information from an upfit subcontractor. And if that didn’t work. Worth said, “I may have to get one (a competing quote) from somewhere else.”

The indictment also discusses statements made by Cox to FBI agents with regard to questions he had about federal grand jury subpoenas that had been served on EEE.

Cox told the FBI agent that he had been “over the drug squad for a long time. I know how all this works. I’ve been to federal court. I’ve put people in federal prison. I know how the processes work.”

In reference to EEE’s bid process with WCSO, Cox stated: “Chris (Worth) would always get my quote first. … And then go and get the other ones so that there was no question of, ‘Well did Chris show him what the quotes were so he could bid lower.’ No, never, ever.”

During the discission with the FBI agent, Cox said he had absolutely no control over who got the bids. He just waited for the call telling him whether or not he got the contract.

“I have nothing to hide here,” he said. “Nothing.”

Cox is also being charged in connection to other statements he made regarding the drug investigations.

At one point, he responded to the FBI agent’s question as to why people think Cox is dirty.

“I mean … well you know … working in drugs a lot of times … you do walk the gray line into … I don’t know, I guess, some people thought or think that you crossed the line at some point or something like that when it’s not,” he said. “I’ve done some things that have been right on the verge of — what. But never nothing dirty.”

Cox could face other serious consequences should he be convicted of the drug charges against him.

According to the Controlled Substances Act, the defendant “shall forfeit to the United States of America … any property constituting or derived from, any proceeds obtained, directly or indirectly, as a result of the said offense, and any property used, or intended to be used, in any manner or part, to commit, or to facilitate the commission of the said offense.”

The act also instructs that if property has been sold, transferred, or diminished in value, the government can go after other assets.

This could include a house, car, or other property.

It is unclear whether charges will be filed against other members of the Sheriff’s Office.

The sheriff has indicated that he is cooperating with authorities, and that action was taken as soon as he was notified of the federal investigation.

Worth is on unpaid administrative leave pending the outcome of the federal inquiry.

FEDS: DEPUTIES WERE LOOSE WITH EVIDENCE

Unmarked weapons stacked in an abandoned shower stall.

Unrecorded narcotics mixed into a basket with properly marked seizures that had been slated for destruction.

Evidence kept in “personal lockers.”

A culture of not following protocol and ignoring requirements for the recording and posting of evidence allowed Wayne County Sheriff’s Office personnel to not only avoid checks and balances, but also permitted “under the radar” access to weapons, money, and drugs, according to the federal indictment released Aug. 30.

According to the report, mishandling of evidence collected from drug arrests and ignoring Sheriff’s Office protocols allowed access to evidence “off the books.”

“In approximately 2012, Worth was promoted to lieutenant in charge of the drug unit, and Cox was promoted to Worth’s second in command. From 2012 to 2016, Worth and Cox operated the drug unit without regard to the procedures and protocols that applied to other deputies,” the indictment reads.

Which, the government alleges, allowed evidence to be seized without the tracking and corresponding case numbers required by WCSO procedures.

According to the indictment, WCSO protocol required deputies to package and mark collected evidence with reference to a computer-generated Official Case Number, which allowed that evidence to be tracked to an actual case number.

WCSO policies also prohibited the submission of evidence into the Evidence Room without an OCA number, and required a written chain of custody to be kept in the event any item of evidence was removed from the Evidence Room, according to the indictment.

After-hours submission procedures were in place, requiring items to be put in a secured area for evidence technicians to label and to secure when they returned to work.

But the secured boxes could only be opened by evidence technicians.

There were also rules requiring deputies to submit evidence to the Evidence Room as soon as possible after seizure and expressly prohibited “the storage of evidence in WCSO personal workspace, lockers, and vehicles.”

According to the indictment, some deputies did not follow those procedures — and Cox knew it.

On the contrary, the government alleges the drug unit often kept evidence “in personal lockers and on designated shelves in the Evidence Room that were not accessible by Evidence Techs.”

The drugs and guns were then off the radar, which allowed drug unit personnel to avoid opening OCA numbers on their cases.

“The Drug Unit’s off-the-books method of handling evidence provided it with the ability to avoid creating any record of a drug suspect’s arrest for drug dealing,” the report reads. “In addition, it allowed members of the Drug Unit the ability to seize drugs and guns from citizens without any accountability for such evidence.”

As a result, the indictment continues, there were “no safeguards in place to stop deputies from taking unmarked evidence, such as firearms, for their personal use.”

And because evidence without an OCA number could not be disposed of officially, the “Drug Unit’s practice was to dispose of evidence offsite without creating an official record.”

That was made possible, in part, the indictment alleges, because Worth, Cox and at least one other member of the drug unit had access to keys and swipe cards that allowed “after-hours entry” into the Evidence Room.

That access allowed deputies to mix unmarked (and unrecorded) drugs into the basket used by evidence techs to temporarily hold drug evidence that had been properly marked and was slated for destruction.

Those uncatalogued items also included firearms, which, the indictment alleges, deputies disposed of by accessing the evidence room after hours and stacking the unmarked weapons in an abandoned shower stall.

“Based on this practice, by 2022, WCSO’s Evidence Techs were unable to ascertain the source of more than 90 firearms located in the Evidence Room without OCA numbers,” the report reads.

The indictment also describes an incident involving a deputy, referred to as Drug Unit Subordinate One (DUS1), who worked for Cox from 2006-2020 at Eastern Emergency Equipment.

The deputy, who is referred to as Cox’s protégé, was promoted in 2011 from patrol to detective in the drug squad.

The indictment notes a case in July 21, 2011, during which Cox participated in the search of a home of a known drug dealer, mentioned in the indictment as the Peele Road Drug Dealer. During that search, Cox and others seized $103,676 in cash.

Cox transported the cash back to the WCSO, where it was held in the Evidence Room.

“Cox and Drug Unit Subordinate One later transported the cash to a local bank and converted it to a cashier’s check,” the indictment alleges. “Worth was listed as a witness to Cox and Drug Unit Subordinate’s handling of the cash.”

Two other interactions with DUS1 are also mentioned in the indictment.

Sometime between 2014 and 2015, Cox allegedly instructed DUS1 to make a digital copy of his girlfriend’s cell phone (also known as “dumping).

In 2015, the indictment alleges, the WCSO conducted an internal investigation of allegations that DUS1 was being paid by a methamphetamine dealer to provide advance warning of planned arrests and searches.

The matter was turned over to the State Bureau of Investigation and assigned to an agent.

Upon hearing about the investigation in January 2016, DUS1 allegedly sent a text to Cox:

“Worst thing is a good buddy that I dumped (Cox’s girlfriend’s) cell phone for anonymously is stabbing me in the back. Now fix this shit before I do.”

According to the indictment, Cox went to “WCSO management” and vouched for DUS1. Soon after, the investigation was closed.

But the bulk of the government’s allegations revolve around alleged relationships between Cox and drug traffickers.

They involve “a significant Goldsboro drug trafficker (Drug Trafficker One)” and another drug trafficker identified as Drug Trafficker Two.

Cox referred to Drug Trafficker One as a confidential informant, although the indictment alleges that “WCSO records do not reflect a CI file ever having been opened by Cox for Drug Trafficker One.”

In 2015, according to the indictment, Cox attempted to forge a relationship with a second drug trafficker, which was unsuccessful.

In 2016, Cox arrested Drug Trafficker Two (DT2) and his girlfriend, but he still refused to cooperate with Cox.

In 2017, DT2 was detained in possession of four ounces of powder cocaine. He agreed to cooperate — and because, according to the indictment, of Cox’s habit of not following WCSO procedure, Cox thwarted any prosecution of DT2 by not opening an Official Case Number (OCA) case.”

Later that month, a WCSO drug unit detective, who was then serving as a task force officer with the Drug Enforcement Agency, requested a copy of the interview relating to DT2’s arrest as part of an investigation into the source of the drugs sold to DT2.

The indictment alleges that Cox instructed a subordinate to create an OCA number, write a report, and to move four ounces of cocaine to the Evidence Room.

No charges were brought against DT2.

According to the indictment, DT2 provided some information to Cox in connection with WCSO’s seizure of drug money, but that by mid-2017 “their relationship had shifted to Cox conspiring to assist DT2’s drug operations.”

“This was accomplished by Cox providing protection under the ruse that DT2 was a CI and passing sensitive law enforcement information to DT2,” the indictment reads.

This is a developing story. For more coverage, follow New Old North here and on our Facebook account @newoldnorth

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Feb. 8, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!