Under the gun

Taj Polack can see the fear in their eyes — the bikini- and swim trunk-clad teenagers barreling toward his backyard on a humid April evening.

Most are barefoot.

Some are screaming.

They jump over his fence — fleeing the barrage of gunshots still ringing out down the street.

Without even taking time to process what he is witnessing, Goldsboro’s mayor pro tem sprints toward the scene of the shooting, a phone up against his ear.

“The kids were running toward me and I’m running to the scene,” Polack said. “As I’m running, I’m calling the police.”

No more than 20 minutes earlier, he had been there — on those same grounds, telling as many of the 100-plus youths who converged on a house off Leslie Street for a Spring Break pool party to make good choices.

His intentions were pure.

In those moments, Polack was not operating as a city councilman or former firefighter.

He was, as he has tried to do every day since taking a job at Goldsboro High School, passing words of wisdom and encouragement from teacher to student.

Many of those in attendance were familiar faces.

“I was literally back there on the premises because I was walking my dog and the smell of weed lured me to go back there and tell my students to be careful,” Polack said. “I knew they probably weren’t going to listen to what I was saying, but I was hoping they would at least be safe. Twenty minutes later, that’s when the gunshots rang out.”

The image he was confronted with when he returned to the scene was far more haunting than dozens of underaged young people passing drugs and alcohol.

Even now, some eight weeks later, he still can’t shake it.

“I saw her. I saw her on the fence,” Polack said “You know, in my time as a firefighter, I’ve seen burned bodies. I’ve seen amputations. But to see that, to see that little girl lying there, that was the grizzliest scene I’ve ever encountered.”

The “her” was 15-year-old Joyonna Pearsall — a former GHS student described by friends and family members as a “light” in their lives.

She was one of six teenagers shot that evening at the party, and the only one who didn’t survive.

“It hit me hard,” Polack said. “Seeing it is something I don’t know how to get past.”

Depending on where you live in the city, you can hear the gunshots.

Often times, the sound of a police cruiser or ambulance follows.

A few hours later, you read the news releases or scroll past the headlines on Facebook.

A murder.

A serious gun-related injury.

In many cases, the victim’s identity is protected — not because family notification is pending, but because the deceased or wounded is a minor.

This isn’t about the Second Amendment or responsible gun ownership.

It’s not about school shootings.

Not in Goldsboro.

This is about hundreds of local teenagers and young adults armed with illegal firearms.

And they are trying to kill each other.

All too often, they succeed.

Balloons are released.

Memorial T-shirts are printed.

Social media tributes are posted.

Every time, this is going to be the last time.

A rally is held.

Community leaders, politicians and representatives from various organizations raise their voices and shout lines to the crowd.

“We’ve had enough,” one will say.

“We’re not going to stand for this anymore,” another screams.

Then, as if it never happened, the community moves on.

Rinse. Repeat.

For a moment, it seemed like Joyonna’s death would be a powder keg moment — that looking at a photograph of an innocent, bright, beautiful young woman cut down long before the prime of her life would be a wakeup call that the gun violence that has become pervasive in Goldsboro had gone too far.

It wasn’t.

Only a few weeks after Joyonna’s death, lawmen responded to an alert from the ShotSpotter gunfire detection system. When they arrived at the scene — at just after noon in broad daylight — along the 500 block of Hinson Street, they found an 18-year-old suffering from a gunshot wound.

Carlos Barrett-Zapata survived the bullet that afternoon.

Two weeks later, a 31-year-old woman wasn’t so fortunate.

Stephanie Lynette Smith was shot May 16 along the 3100 block of Cashwell Drive. Hours later, she was declared dead at UNC Health Lenoir. Her alleged murderer was only 23 years old.

Gunshots have been heard across the city seemingly every day since.

On May 28, in the middle of the afternoon, a 20- and 24-year-old allegedly robbed the Family Dollar on Wayne Memorial Drive — shooting and killing 46-year-old employee Alexander Thomas.

A few hours later, 29-year-old Antoinette Sauls and two 15-year-old boys were “grazed by bullets” when shots were fired on Seymour Drive.

“Too many people are looking at this young girl who just died like they’re shocked. Why are you shocked? In my city, it’s gotten worse, drastically I’d say, in the last two years,” Polack said “Joyonna, she wasn’t the first. And she wasn’t the last. But this gained momentum and news coverage because, let’s call it what it was, it was a mass shooting. But even still, where are those people now? Where are the ones who were at the rallies and the marches? If they’re out there, they’re awfully quiet.”

Data collected by the Goldsboro Police Department and provided to New Old North tells a story.

Since 2020, ShotSpotter has alerted lawmen to more than 2,300 shots-fired incidents inside the city limits.

As of May 30, there had been 355 this year alone.

That’s more than 2.3 shootings a day.

Fortunately, not every ShotSpotter alert results in a homicide investigation.

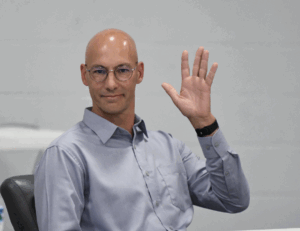

But Police Chief Mike West would tell you that the numbers are jarring — that with every shot fired comes the potential of loss of life.

“I can’t paint the picture for (the public) of what truly goes on because I run the risk of panicking the community,” he said. “There’s absolutely no respect on the streets anymore. The hatred is unbelievable. There is absolutely no respect out here whatsoever. There is no respect for human life.”

Knowing that makes every day stressful — not just for the chief, but for the men and women under his command.

“Every day, I’m concerned about the officers on the street just like they are. Every day they come to work, more so than when I started, they feel that danger,” he said. “Now, just with what we’re seeing in the community — and not just our community, but communities across the nation — this is a very concerning time. You think constantly about, ‘What if something happens? What if I get a phone call?’ Every time my phone rings or I get a text message, is this going to be the message I get that’s, ‘One of your officers has been injured or killed.’ It’s that dangerous out there.”

And the tide shifted in a relatively short amount of time.

Before COVID-19, community policing kept much of the violence at bay, West said.

Officers could essentially embed in high-crime communities and act as mentors to at-risk youths.

“But during COVID, everybody pulled back from our community policing. My officers couldn’t make contact with people face to face,” West said. “And the youth lost, both because of that and because a lot of community programs stepped back. Well, it’s coming around now. Now, we’ve got to pay for it.”

Once pandemic concerns subsided, staffing woes within the department compounded the problem. There simply were not — and still are not — enough officers to commit to the type of relationship-building on the streets that reduces the violence.

“We had dropped crime consistently since 2016 … and now we’re on the uptick. But where we excelled was one-on-one engagement with the community,” West said. “When I’m staffed up, officers have time in between calls for service to get out and do a pickup basketball game with some youth out in the neighborhoods or get out and talk with the elderly. But for the last three years, we’ve had in excess of 25 vacancies.”

Currently, GPD is 34 officers down.

That shortage also forced West to dissolve the Selective Enforcement and Gang Suppression units.

“I’ve had to take those people who were in those units to stand patrol back up,” he said. “Where we’re going to suffer is the long game. It’s the community policing and being available to these youth in the community who need help — to be that father figure that takes just 10 minutes. The officers I have now can do that very well. We just don’t have the consistency because they’re thumping calls all the time.”

So why is there a shortage?

It is safe to assume national news events that have pitted communities and activists against law enforcement haven’t helped, West said.

But those who still want to serve are choosing, more and more, to join forces in neighboring communities that pay far more.

“Whenever I see our recruiting flyer go out, I can’t help but be disappointed in thinking that it’s not going to do us a bit of good when my starting salary is at 40 (thousand dollars a year) and I can go to Rocky Mount right now — new officer, as green as a gourd — and make the same amount of money there that a 16-year veteran here, with rank, is currently making,” West said. “It’s a big issue. It’s a really big issue. I understand that the city is not made of money. I get that. And I understand that people don’t want to throw their tax dollars at it. I get that. But we’ve watched it. We’ve watched the crime numbers go up. So, the (staffing shortage) is very concerning — and I don’t see a lot of applications coming in.”

•

A year to the day before Joyonna was laid to rest, the chairman of the Wayne County Juvenile Crime Prevention Council delivered a stark warning to the Board of Commissioners.

“If we get through this thing and it sounds like I’m scaring you, I’m doing my job,” Dustin Pittman said.

He explained that the role of the JCPC is not to put teenagers in jail. Instead, juvenile courts hope that intervention can steer them in a better direction.

“It helps to understand their home situation. It helps us understand their needs and what are the risks they are facing. We’re not looking to punish a juvenile that comes to court. We’re looking to get behind the issue — to address the problem so that this juvenile doesn’t come back,” he said. “We want to make sure we understand, ‘What is the trigger? Why are you doing this? Where is this coming from?’ Then, we try our best to put services in place in that home situation … to make sure we address the problem.”

But then, he delivered the data — numbers that illustrate what the community is facing.

Pittman told the board that of the county’s juvenile offenders, 58.1 percent had a previous misdemeanor or felony charge, a number three times the state average and one that reflected a 150-percent jump over the last four years.

He shared statistics relating to their home lives — that 36 percent had attempted to run away from home and 37 percent of their parents reported that they are unable to supervise their children.

“They are willing. They want to. But they can’t,” Pittman said. “Now, this might be the parent that is working two or three jobs … or this might be the parent with substance abuse concerns or mental health concerns that just lacks that ability.”

Eighty percent of the juvenile offenders reported a “substance use handicap” of some sort, primarily marijuana use.

Nearly 90 percent of offenders had a mental health diagnosis.

But the two numbers that shook the room came near the end of his presentation.

Three-quarters of them had “significant behavioral concerns in the school system,” defined as having been suspended for at least 10 days in the past school year.

And 58 percent either self-identify as a gang member or are “directly associated” with gang members.

“Fifty-eight percent folks. That number has increased 250 percent over the last four years. (That’s) the one that I’m here for. (That’s) the reason I’m here today. That’s where we are. Things are continuing to get worse.”

•

Delavisha Faison can hear the pain in their voices — the dozens who called her to deliver the news about Joyonna’s death on a humid April evening.

Most can’t believe that shots were fired at the party.

Some are crying.

She knows that had she not taken her teenage son, teenage family members and their friends to Myrtle Beach to celebrate Spring Break, those phone calls could very well have marked a much more personal tragedy.

“They would have been at those parties.

That’s the hurting thing to me. And just having a teenage son, it makes me sit on the edge of my seat all the time,” Faison said. “Everything seems to be a little worse than it has been in the past. I’m not really sure what the difference is.”

As the CEO of Mentoring Futures NC, a non-profit that seeks to fill the void in young lives when they don’t have a mentor or family support, she has buried far too many mentees in her lifetime.

“I’ve lost a lot of my babies to gun violence and every time I read about it or someone sends me a text or an email, it just breaks my heart over and over again. It takes me back to those I’ve lost,” she said. “It’s really something that we really have to get a hold of or, sadly, we’re going to lose this battle to the streets.”

She is among those searching for answers as the city faces a dramatic increase in gun violence.

“They’re bringing these guns and things to parties and other public places,” Faison said. “How are they getting them?”

And where are their parents?

“It’s hard, but again, it goes back to accountability — knowing where your kids are, knowing what’s going on in their lives,” she said. “That is one way that I kind of try to help parents — making sure they are accountable for what their kids are doing.”

But the neighborhoods are only part of the problem.

Faison, Polack and others would tell you that from the moment a youth steps onto the school bus in the morning, he or she is conditioned to believe they can get away with reckless and violent behavior.

“At the end of the day, it comes down to responsible adults. That’s from parents, that’s from the community, that’s from teachers and principals. Everyone has to try to come to the same page if we’re going to make a difference,” Faison said. “But when they get on these buses, when they get to these schools, if no one is holding these kids accountable for what’s going on, they think it’s OK to do. They think it’s OK to fight. Because what’s going to happen? I’m just gonna get a slap on the wrist. So, to have those principals and some of those teachers just slap their hands, it sends them the wrong message. Then, that behavior goes back home and to parties.”

And then, it comes right back to school campuses.

“Where before, sadly, they were on the corners and they were in the streets and as parents, you could keep your children in the house, now, they are at school,” she said. “You have gangs and all that going on at the school. That’s where the leaders in the schools have to step in.”

Polack agrees.

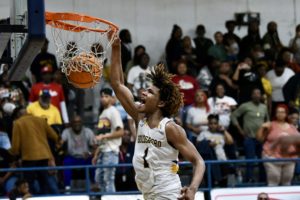

“What’s happening in these schools is, they are pacifying these kids and play favorites due to athleticism. And the priority, there again, is not put on education and accountability. It’s, ‘Who can jump the highest?’ and ‘Who can throw the ball the farthest?’” he said. “It’s unfortunate because other kids see that … and they act out because they’re jealous that they don’t have those gifts. But also, a lot of it is parenting. I was literally (at the pool party) before this thing happened and there were parents literally doing some of the same things I discourage my (students) from doing. So, are they going to listen to the teacher who’s discouraging them or are they gonna listen to the parent that’s allowing them to do those things?”

That, Faison said, is what makes a solution so difficult to find.

It will take everyone “being on the same page” to begin what she believes will be a long struggle to save the city’s youths.

“We have so many that come in when something happens, but those same ones who say, ‘We’re here. We’re gonna help these kids,’ they leave,” Faison said. “I love these kids. I have dedicated my life to them — to be a positive role model and helping them in any way that I can — but a lot of times we have these people come in when something happens, but when we need them the most, when these kids need them the most, we can’t find anybody. The leaders? Where are they?”

And Polack, who remains haunted by what he found when he arrived at the scene of that Spring Break pool party, said to do nothing dishonors the memories of all those who have fallen victim to what he considers a gun epidemic in the city that raised him.

“It’s unfortunate that the community can come together organization-wise when it comes to a date for a balloon release, the memorial shirt sizes, the image on the shirt,” he said. “Everybody is organized in the face of tragedy. But where’s the organization to be proactive?”

Without that organization — without a village wrapping its arms around the community’s youth — Faison fears the battle will be lost.

“If we don’t do it, it’s scary to think about,” she said. “Can we trust the streets to raise our children?”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Feb. 8, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

Final Four!