Ray of hope

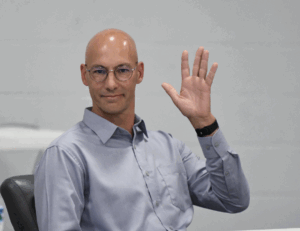

Ray Thomas’ eyes swell and tears begin to form.

Sitting at the head of a long dining room table, he looks down — taking in, albeit briefly, the fact that he is flanked by people he didn’t know a year ago but has come to love.

In some ways, they saved him. They gave him a job, a purpose, and most recently, a place to call home.

But those who have come to understand the unlikely relationship between Cry Freedom Missions CEO Beverly Weeks, COO Jonathan Chavous and the man they simply call “Mr. Ray,” know that he has done something for them, too.

He validates their faith in people — in the power of trust and human bonds.

He energizes them on days when the difficult work to “reach, rescue and restore those who have been trafficked” weighs heavy.

He sets an example of how to approach life — never meeting a stranger; perfecting his work not for a paycheck, but for the pride that comes with a job well done.

Ray might not call showing up at the Cry Freedom Missions Shoppe & Café fate, but when you ask him how it came to be, he raises his head and smiles.

He glances up and lifts a finger skyward — a purple “I LOVE JESUS” lanyard hanging from his neck.

“He got me,” he says. “I’m serious now. I used to be around bad people, but He stopped me. Something come to me and hit me and said, ‘You go the good way.’”

•

It started shortly after Cry Freedom was gifted an old theater along Center Street — a neglected part of Goldsboro’s history in the middle of downtown that was in desperate need of a second act.

“Ray came to us when the building was under construction,” Beverly said. “He said, ‘Y’all need me.’ It wasn’t, ‘Can I have a handout?’ It wasn’t, ‘Can I have free money?’ It wasn’t, ‘Can I have free food or free drink?’ It was, ‘I want to work. Put me to work.’”

It wasn’t an easy decision. Providing a job for an older, disabled man is not a part of the Cry Freedom mission statement.

“Our mission is to reach, rescue and restore those who have been trafficked,” Beverly said. “This didn’t fall into that. Mr. Ray has never been trafficked.”

But there was just something about him.

Get him talking and you start to understand.

His eyes don’t lie.

He exudes a joy and pride that are both inspiring and contagious.

And despite his need for help, he wanted to do all he could for everyone around him.

“That’s always a sign, when you see people who don’t just think about themselves,” Jonathan said. “You want to do more for those individuals. And with Ray, he was always looking out for people on the street. He was always looking out for people around here. He would give them stuff, what little he had to give. So, for me, it was, ‘How can I help him out at the same time he’s helping everyone else?’”

The job at Cry Freedom was the first step.

•

Growing up as one of five children in a single-mother household, Ray learned the value of hard work.

His mother was a stickler for cleanliness.

“Don’t bring your shoes into the house,” Ray said. “Better not.”

And both his mother and grandmother taught him about faith and unconditional love.

“Grandma made us go (to church),” Ray said. “She told my mama, ‘Get ’em up. Don’t let ’em lay around this house.’ I loved (my grandmother) so much. I would have to go see her all the time.”

Given his need for assistance, he lived with his mother until her death — and then, with his grandmother until hers.

“When he lost his mom, things started going down,” his cousin Patricia Thomas Wynn said.

And after moving in with family member after family member — Patricia’s grandmother, his aunt — until their passings, he risked no longer having a reliable place to call home.

Beverly and Jonathan did not know those details when they hired Ray.

In the beginning, he was simply someone who craved an opportunity to be part of something.

It paid off.

He keeps the store immaculate — with a torrent of sweeping, mopping, taking out trash and washing windows.

“I keep their place real clean for them and when people come and visits their place, they talk about it. Sure do. They talk about it,” Ray said. “I don’t like to sit down. No sir. It’s not me. You’ve got the wrong one.”

And he is constantly keeping watch over customers and coworkers.

“In the evenings, he watches the girls who work at (the store) walk to their cars to make sure they’re OK,” Jonathan said. “He doesn’t let anyone mess with them.”

It’s part of Ray’s protective instinct that, after hearing his story, makes sense.

After all, his mother and grandmother kept him safe for decades.

•

It’s nearly 11 in the evening and Beverly’s phone rings.

It’s pouring down rain outside, and Ray is standing in it.

“He called me (that) night and said, ‘I need help,” Beverly said. “I said, ‘Ray, where are you at?’ He said, ‘I’m in the woods.’ That was it for me.”

She couldn’t bear knowing that a man like Ray had no place to go.

So, she and Jonathan decided to find him one.

There was just one problem.

“I don’t like to ask for nothing. (Beverly) will call me and say, ‘Tell one of the girls I said to let you get something to eat before you leave.’ I don’t even pay it no attention,” Ray said. “I don’t like to go in someone’s building and they say, ‘Mr. Ray, there goes a soda right there. Get you one.’ I don’t pay it no mind. That ain’t me.”

•

In the historic Waynesborough House, just across the street from the Cry Freedom shop, Ray flips on the television and shows off his new apartment.

It’s a simple place — a bed, nightstand, small kitchen, recliner, mirror, sink and television all located within feet of each other.

But it’s his.

Ray only accepted it because he felt like he earned it through the many hours he dedicates every day to his job.

“And he did,” Beverly said.

Watching him inside the space, it is clear just how proud he is to have somewhere to call his own — somewhere he feels safe.

“I don’t bother people. I like to come over to work and once I leave from there, I go take me a shower and lay down — turn the TV on “In the Heat of the Night” or Chuck Norris,” Ray said. “I want to stay to myself. If you don’t, that’s when the bad people start coming and try to get you to go with them.”

•

Beverly’s eyes swell and tears begin to form.

She keeps her eyes focused on Mr. Ray, trying to explain what makes him so special.

“We fell in love with him. He’s like a brother to me,” she says, her voice breaking. “I fell in love with his heart. I fell in love with the fact that not only was he a hard worker, I felt like he needed love. For us, we were compelled to love the broken at all costs, because at the end of the day, we’re all broken people.”

Moments later, as if those words had sparked something inside her mind, she turns to Jonathan.

“He has some disabilities that make him vulnerable to being preyed upon. Isn’t it ironic that that is the girls we are serving as well?” she says. “They have addictions. They have mental disabilities. That makes them vulnerable … and we saw that in Ray and wanted to step forward and help him out.”

She had no idea he would become family.

But it’s a sacred bond — something she, Jonathan and Ray carry with them every day.

“He calls me every night to tell me the girls are OK — that they made it to their cars safely,” Beverly says, tears still in her eyes. “We talk for about five or ten minutes.”

And then, they exchange the same words.

Words that represent far more than either party bargained for the day a man showed up outside an under-construction former theater in a historic downtown and asked for a chance to prove he had something essential to offer.

“We end our conversation the same way every night. Goodnight, I love you,” Beverly says. “He always responds, ‘Goodnight. I love you, too.’”

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — Feb. 8, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

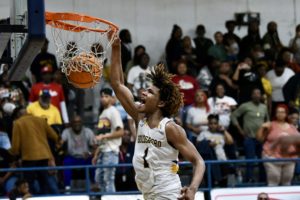

Final Four!