Williams takes on Constitution, public records law

District 1 Councilman Antonio Williams attempted to educate senior city staff members — and Mayor Chuck Allen — on the Constitution and public records law Monday during a pre-board meeting work session during a conversation about what he characterized as his “personal emails.”

But Williams’ argument raised several questions about his classification of the communication and his interpretation of how information is or is not protected under state and federal law.

The latest back-and-forth among council members started with a citizen visiting the city’s official website and filling out a form they intended to send to the District 1 representative — not knowing that those completed entries are emailed to the city clerk’s office for initial review. Protocol established when the site was created several years ago requires the clerk’s office to forward those forms to the intended recipient — in this case, Williams — but also to pass them along to the department best suited to rectify the situation at hand.

When City Clerk Melissa Capps and her deputy, Laura Getz, reviewed the correspondence, noting that it contained a public safety concern, they followed mandatory reporting requirements and passed the information to their boss, City Manager Tim Salmon. He then was bound to the same requirement of mandatory reporting and sent it to Williams, Allen and the police chief.

“This particular case, the clerks brought it to my attention because it had to do with someone’s life in jeopardy, abuse of family members. I have a moral, if not legal, authority to do mandatory reporting once I find something like that out,” Salmon said. “Our procedures are if something comes in, to a council member or a citizen request, it goes to our clerks. Our clerks see every one of them and they send them to the appropriate person.”

And that is what Williams was upset about.

“I received an email from a citizen, and it was a confidential email that was sent directly to me. Without going into the details of this email, this email was sent to the city manager from one of our clerks and it was serious issues that could have caused harm to this individual,” he said. “In turn, this email … the city manager sent it to you, Mayor Allen, and also it was sent to a third party. So, my concerns are, ‘Why is someone looking at my personal emails, where the citizens are supposed to confide in whomever they’re sending it to and trust them? What’s the protocol pertaining to that? I can understand a city manager, he may have to look at employees’ emails, but we are not his employee. And our clerk had no right … to forward this information that was confidential.”

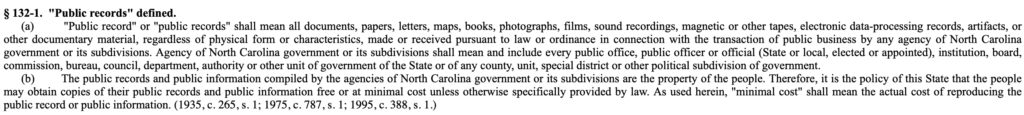

In reality, the “email” was not sent directly to Williams. And because the information was submitted using the city’s official website, it instantly became public record, as defined by state statute.

Salmon attempted to explain those facts to Williams.

“As far as procedurally, anything that is sent into our government website is public information,” he said. “It’s public.”

But the councilman disagreed — and argued, incorrectly, that Salmon didn’t understand the law.

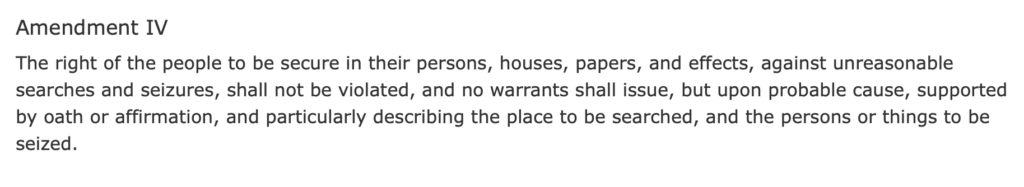

“It’s only public information when it’s dealing with public business. It was never public business at that point,” Williams said. “It’s a Fourth Amendment rule. After 180 days, then anyone can read those emails. After 180 days. Not beforehand. Not without a subpoena.”

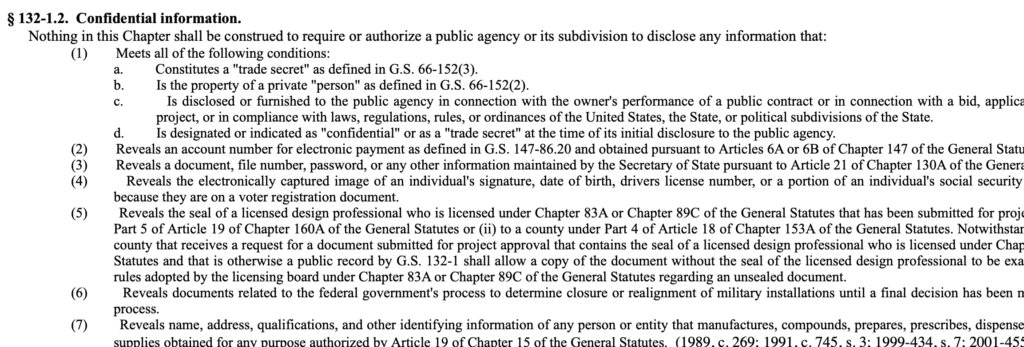

The Fourth Amendment, which deals with privacy as it relates to unlawful search and seizure, does not address public information. Here it is:

In fact, nowhere in the Constitution is privacy of emails sent to public officials addressed.

Furthermore, all emails sent to or from members of the City Council to or from their government accounts are considered public business and therefore are, by definition, public record. So are letters. So are photographs. So are records of charges made using city funds. So are sound recordings.

When it comes to “confidentiality,” state statute defines what qualifies as public record.

Whether or not the council will vote to change the protocol — thereby ensuring communications meant for someone end up with that person and that person alone — public record law is clear. In other words, even if the chain of custody was changed by the board, a request from the media or a member of the public — any member of the public — would still subject the information to public records law.

“You can change the process if you want,” Salmon said.

Changing public records law, however, would require an act of the General Assembly and the signature of the governor.

A loaded discussion

Fighting for their lives

Goldsboro loses a giant

“I’m a flippin’ hurricane!”

Public Notices — March 8, 2026

Belting it out

Legendary

In her Nana’s image